Because we wanted to understand the long-term implications of the format choice, we adopted the life-cycle approach. In the analysis that follows, we track the total nonsubscription costs over the course of 26 years of accessioning one year of a typical periodical. One way to think about this analytical technique is to imagine following a single year’s worth of a given periodical subscription, tracking its total nonsubscription costs over time. The costs reported therefore represent the implicit long-term financial commitment made at the point of acquisitions for a given year of a given periodical. It is by comparing these total costs over time that we can best compare the nonsubscription cost implications of the two formats.

The choice to examine 26 years was arbitrary. It was built on the assumption that a print periodical would be held for one year as a current issue and for 25 years as a backfile, and that an electronic periodical would be maintained for an equal period of time. Any other time horizon could have been selected.

We report life-cycle costs as a net present value. The net present value allows us to calculate the amount of today’s money that, after interest is added, will be adequate for a future need. It allows for the easy comparison of two future cost streams, such as the life-cycle costs of the print and electronic formats. For costs in subsequent years, we used a discount rate of 5%.28

The purpose of this exercise was to make possible a comparison between the print and electronic formats at each library. This approach cannot be expected to predict costs for different libraries or for the same libraries operating under alternate procedures or processes. The life-cycle approach allows us to calculate the costs over the course of time for each of the participating libraries, if they continue to operate under the same set of processes as they do today. Moreover, we have focused on developing internally consistent measurements at each library and on allowing for comparison by format. Our data are most valuable for making this comparison, rather than for examining absolute costs or patterns across the libraries. The findings that this section yields will certainly offer direction and guidance to other libraries, but any number of variables, including different levels of service and usage, lead to variance among the costs of the participating libraries and might cause costs at other libraries to differ from the costs presented here.

Specific formulae are outlined in the sections that follow for the two formats. In general, however, our work involved decomposing the budgetary data found in the previous section into one-time expenditures and recurring expenditures. We then allocated these as they could be expected to occur in the first and subsequent years.

By presenting separately the data for the first year and for subsequent years, we make it possible for interested parties to project out as many years as they see fit. For example, a library that is focused on its role as a long-term steward of its periodicals collection might combine the one-time cost with 100 years of the ongoing costs to compare the life-cycle costs of the print and electronic formats. In the subsections that follow, we present the formulae and the findings and use them to compare the two formats.

Life-Cycle Formulae

We began our analysis of print periodicals with the one-time costs, that is, those costs that can be expected to take place only once during the life cycle. For the typical print periodical, most of these costs are experienced in the first year. They include all activities associated with current issues and certain presumptively one-time costs associated with preparing the backfile volumes. We included one year of the following costs:

- all staff costs on the current issue format

- staff costs for those activities on the backfile format that are one-time in nature, namely

- collection development

- licensing and negotiations

- subscription processing, routine renewal, and termination

- receipt and check-in

- routing of issues and/or tables of contents

- cataloging

- linking services

- physical processing

- depreciation of staff workstations, allocated on the same basis as the staff costs

- total cost of binding

- total cost of subscription agents and

- cost of space occupied by the current issues reading room during the year.

For each library, we divided the sum of these costs by the number of print current issues titles to reach the one-time cost per title.

We then determined the ongoing costs. These are costs that will recur every year for every bound volume of every title. Our approach entailed calculating the total annual ongoing costs experienced by each library. This was determined by summing

- staff costs on the backfile format for ongoing services, calculated on a dollar-per-year basis, namely

- stacks maintenance

- circulation

- reference and research

- user instruction

- reservation

- other activities

- depreciation of staff workstations, allocated on the same basis as the staff costs

- depreciation of publicly available workstations, allocated at 2% to print periodicals

- annual cost of storage space in an off-campus facility, calculated on a dollar-per-year basis and

- annual cost of shelving, calculated on a dollar-per-year basis.

For each library, we divided the sum of these costs by the number of volumes held in the backfile to reach the annual ongoing cost per volume.

We then combined the one-time cost per title and the annual ongoing cost per volume that have just been reported to yield the life-cycle cost. Because these two figures were reported on two different unit bases (titles in one case and volumes in the other), we had to take an extra step to bring them together in the life cycle. We used the ratio of bindings to titles for this purpose. This was an important step, because not every print title will yield one bound volume per year. Some periodical titles are not bound, are not bound every year, have multiple subscriptions, or yield multiple bound volumes per subscription due to their length.

The ultimate life-cycle formula for one title is as follows:

| Print Life-cycle Cost | = | 1*(One-time cost per title) + Net Present Value of 25 Years of [(Bindings per title)*(Annual ongoing cost per volume)] |

The life-cycle cost analysis for the electronic format is fundamentally similar, although the structure of the format necessitates some differences. There is no natural distinction between current issues and backfiles, which makes some of the distinctions between ongoing and one-time costs less intuitive. We nevertheless were able to group activities by those that are fundamentally one-time in nature and by those that are recurring in nature. This allowed us to perform an analysis that mirrored our estimates for the print format.

We began our analysis of the electronic life cycle with those activities that are expected to take place only once for a given year of a given title. We included one year of the following costs:

- staff costs for those activities on the electronic format that are effectively one-time in nature, namely

- collections development

- receipt and check-in

- cataloging

- linking services

- an allocation of staff costs for two activities that are principally (we estimate 75%) one-time in nature but have recurring components to them as well29

- 75% of negotiations and licensing

- 75% of subscription processing and

- the depreciation of staff workstations, allocated on the same basis as the staff costs.

For each library, we divided the sum of these costs by the total number of electronic titles to reach the one-time cost per title.

For activities that are recurring or ongoing, we developed a mechanism to spread costs across the multiple years of the electronic periodicals available on campus. For these, we determined the nature of the recurrence, assuming an average of five years of content for every electronic periodical currently provided on campuses. Use of electronic journals over the five years represents use of one-year-old through five-year-old titles. The recurring costs in our data are therefore assumed to be spread across five years.

Of the recurring costs, we first considered separately those that are believed not to vary by usage. These include

- staff costs for those activities on the electronic format that are effectively recurring, unrelated to usage, in nature

- routing

- preservation

- other activities

- an allocation of staff costs for two activities that are principally (we estimate 25%) one-time in nature but have recurring components to them as well30

- 25% of negotiations and licensing

- 25% of subscription processing and

- depreciation of staff workstations, allocated on the same basis as the staff costs.

For each library, we divided the annual expenditure on these activities by five to achieve an average cost per title per year. We divided this annual total by the number of titles to reach the annual ongoing cost per title.

Finally, some costs vary based on the degree of usage. These include

- staff costs for those activities on the electronic format that are effectively recurring, related to usage, namely

- circulation

- reference and research

- user instruction

- the depreciation of staff workstations, allocated on the same basis as the staff costs and

- the depreciation of publicly available workstations, allocated at 6% to electronic periodicals.

We called this sum the use-related cost per title.31 We expect usage of electronic periodicals to decay over time, as is also typical with print. Our data are, however, believed to include only five years of titles. Recent surveys in three universities suggest that there is only about 21% more use beyond the five years.32 Thus, the use-related cost per title (circulation, reference and research, and user instruction) is multiplied by 1.21 in the formula.

The ultimate life-cycle formula for one electronic title is:

| Electronic Life-cycle Cost | = | 1*(One-time cost per title) + Net Present Value of 25 Years of (Annual ongoing cost per title) + 1.21*(Use-related cost per title) |

The Life-Cycle Findings

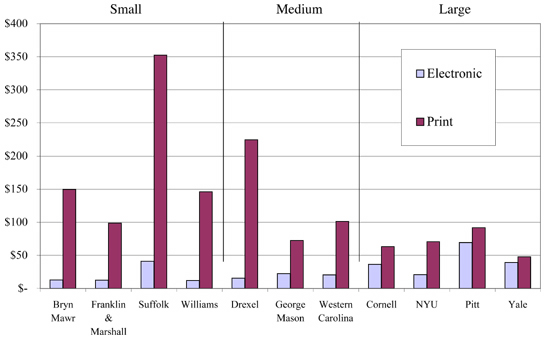

The cost comparison in table 6 and figure 7 indicates that the long-term financial commitment associated with accessioning one year of a periodical is lower for the electronic format than for print at every library in our study. There is strong reason to conclude that the electronic format brings a reduction in the nonsubscription costs of periodicals across the board.

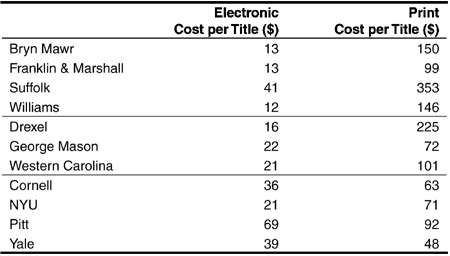

Table 6. 25-year costs allocated to print and electronic periodicals, per title

Fig. 7. Relationship between print and electronic 25-year life-cycle costs

The potential savings are most pronounced at the smaller institutions. This development is consistent with our understanding of these libraries. Because the larger libraries have long benefited from economies of scale in their print operations,33 the relative savings to be generated from the further economies brought by electronic periodicals are simply not as great as they are at smaller libraries. This finding should not be discouraging to the larger libraries, which nevertheless would stand to save, but seems compelling for the smaller libraries, for which there appear to be opportunities to realize roughly the same per-title cost basis as the larger libraries.

In examining the life-cycle findings, one must recall that three of the large libraries chose not to include significant parts of their science, technical, and medical (STM) and law collections in the reported data. Many STM and law titles produce quite a number of bound backfile volumes per year. These titles would have brought up the ratio of bindings per title, had they been included in our dataset. To think about them separately, we should consider that, in addition to the one-time costs, many of these titles might yield the annual costs of up to 20 volumes per year. The absence of these collections from our data clearly has the effect of reducing the reported life-cycle cost of the print format at these libraries. Including these collections would have yielded modestly higher print unit costs than those reported here, for Cornell, NYU, and Yale.34

Moreover, because we charged space at the rate of a highly efficient high-density off-campus facility, the per-title implications for the costs associated with reduced space requirements are rather small. While we believe that this is the most appropriate representation of the likely savings (for the reasons discussed in the Study Design section), some institutions might find that a switch to electronic would relieve them from constructing some amount of costly on-campus browsable shelving.

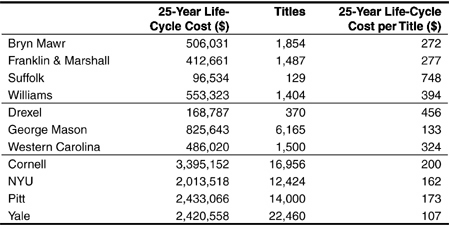

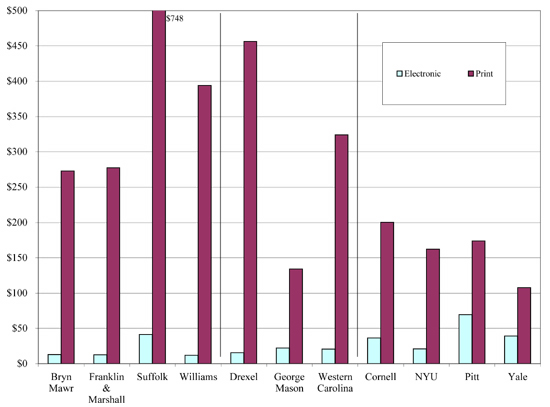

In the previous tables and figures, we assumed that print backfile volumes are stored off-campus. This yields a construction cost of approximately $2.50 per volume. Storing volumes on campus, in a newly constructed Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)-compliant facility, is estimated to cost an average of $250 per volume. On this basis, we have developed table 7, which includes the print life-cycle calculations exactly as they were performed above, but using the figure for newly constructed on-campus storage. For a comparison with the electronic life-cycle cost, see figure 8.

Table 7: Total annual cost allocated to backfiles of print periodicals, per title, assuming on-campus, ADA-compliant, newly constructed library facility

Fig. 8. Relationship between print and electronic 25-year life-cycle costs, assuming on-campus, ADA-compliant, newly constructed library facility

The cost comparison is far more dramatic if print backfiles are stored on campus. But regardless of whether their backfiles are stored on or off campus, electronic periodicals collections are less costly, on a unit cost life-cycle basis, than print collections. This life-cycle analysis has offered a window into the ways in which the nonsubscription costs vary on a unit basis. Before reaching any conclusions on the basis of these findings, however, it is necessary to consider-as we will in the following two sections-how these life-cycle unit costs may affect total library expenditures on nonsubscription periodicals. For the following sections, in which we model some of the possible effects of the life-cycle analysis, we hold to the assumption that storage costs for print backfiles are at the rate of a high-efficiency off-campus facility.

FOOTNOTES

28 Discount rates of 3% and 7% were also tested, without significant differences in the direction or scale of the results.

29 While the allocation of 75% of these costs here is an approximation, we believe that most of the costs of these two activities in the electronic format are one-time in character.Although renegotiations and processing take place on a recurring basis for electronic periodicals, it is important to distinguish new years of a given periodical from previous years. These two categories of recurring costs are properly attributed in large measure to the new years of the title, not to the previously accessible years.

30 For explanation, see footnote 29.

31 It is necessary to segregate the use-related costs only for the electronic format. The backfiles of the print format date back through the life span of the periodical. For this reason, the natural decay in usage is built into the use-related costs of the print format periodicals. For the electronic format, however, the frequent lack of backfiles means that the anticipated usage decay was not built into our data and therefore must be estimated.

32 Surveys were conducted with University of Tennessee, Drexel University, and University of Pittsburgh. King et al. 2003a.

33 These economies of scale characterize large, centralized operations, and a library such as Yale, whose data in this study include only the large central collections at Sterling Memorial Library, exhibits such economies dramatically. However, the data for other large institutions, such as the University of Pittsburgh, include, in addition to an extremely efficient central library, a significant number of small libraries are spread across multiple campuses-thus exhibiting higher average costs per title. For more detail about the economies of scale that we observed, please see the section entitled Total Costs and the Transition Path.

34 Another effect of excluding the data of certain collections from some of the libraries is to undercount the cost of titles for which duplicate subscriptions may exist in the excluded collections. Had all duplicates been included, total costs for the same number of titles would have risen. This would also have led to at least modestly higher print unit costs being reported for the affected schools.