As we have just seen, the electronic format’s substantially lower life-cycle costs, in comparison with those of print, are striking. Measured on a unit basis, i.e., per title, these costs may be reduced by as much as 90% or more. Other things equal, our unit-cost findings imply that the total nonsubscription cost, on a life-cycle basis, will also be lower in the electronic format than in the print. In this section, we develop a number of models that suggest how this might be the case, while also offering a number of cautionary notes.

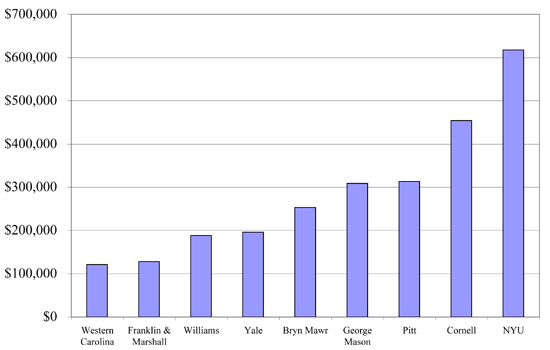

To measure the total potential cost effects of these differentials, we estimated the decrease in the implicit long-term financial commitment under the hypothetical case of a complete transition from print to electronic format for periodicals. To do so, we multiplied the number of current print titles by the cost differentials between the print and electronic life-cycle figures. This yielded the amount by which the total financial commitment decreases for every year’s worth of acquisitions (see figure 9). These figures do not include the collections, including law and STM, that were excluded from a number of these libraries, and therefore omit associated cost differentials. The total differentials at Drexel and Suffolk would be at the low end of the spectrum because they have already transitioned to the electronic format and few print periodicals remain. For them, many of the cost advantages of a transition have already been realized.

Fig. 9. One year after the transition from print to electronic (total cost differential over 25-year life cycle)

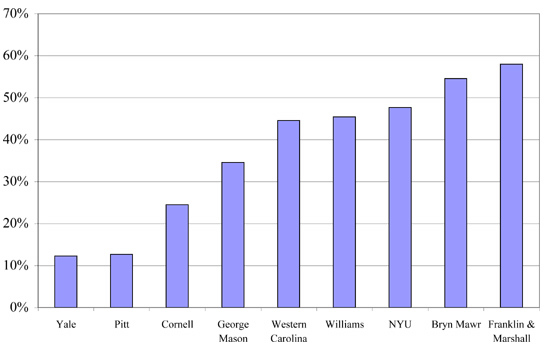

Fig. 10. Total 25-year life-cycle cost differentials as a percentage of annual nonsubscription periodicals expenditures

We estimated in figure 10 the cost savings within each library that can potentially be realized, as a percentage of total nonsubscription costs. To do so, we divided the figures presented in figure 9 into the total annual nonsubscription costs from figure 5. We thereby compared the cost effect, which is achieved at various points across the life cycle, with the actual annual expenditures. One cannot assume that these rates of cost reduction could be expected in the initial years of a transition, since the cost effects take place over the course of the life cycle.

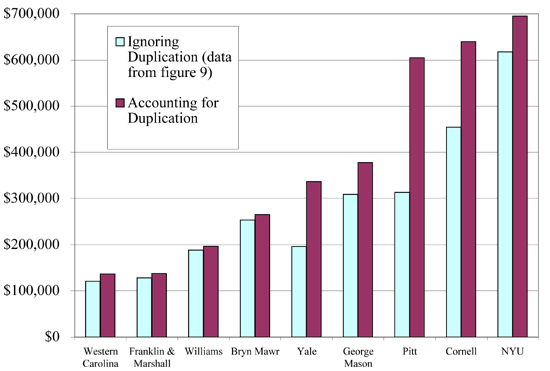

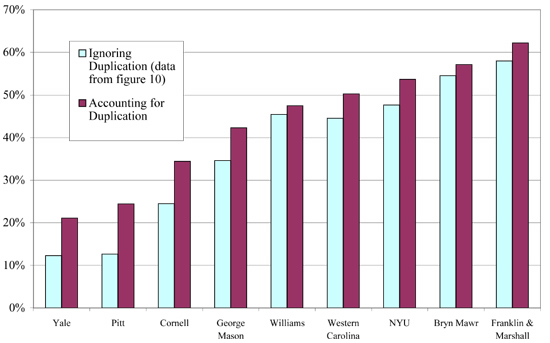

There is significant duplication of print and electronic titles at many of these libraries (see Withers 2003, 934). We therefore have estimated rates of duplication and assumed that, for titles that are received in both formats, there would be a savings in the cost for print without a corresponding added cost for electronic. Our assumptions are that 16% of print titles are duplicated in electronic at Yale, 30% at Cornell, NYU, and Pitt, and 50% at the medium and small institutions. Figures 11 and 12 present the cost differentials under this set of assumptions.

Figures 11 and 12 represent our best estimate for the long-term effect of the transition on the libraries in the study. Accounting for estimated duplication, we found cost differentials exceeding 50% at four of the libraries and differentials of 20% or greater in all nine libraries that have yet to make the full transition. Although the absolute amount of the differential is larger at the large libraries, the rates of savings tend to be lower at these large libraries. Differentials on the order of $100,000 or more are expected to be generated for every year that the library has an electronic-only collection, at every library that undergoes a transition.

Fig. 11. One year after the transition from print to electronic (total cost differential over 25-year life cycle), accounting for duplication between print and electronic formats

Fig. 12. Total 25-year life-cycle cost differentials as a percentage of annual nonsubscription periodicals expenditures, accounting for duplication between print and electronic formats

While this represents our best estimate of the ultimate cost effects, it is important to bear in mind the scale effects that are at work. The data reported in the two figures above assume a complete transition, and it may be years, if ever, before the majority of users at many of the libraries in this study would demand (or tolerate) such an action.35 During a transition, if it were to be gradual, print subscriptions would decline but not be eliminated and so the associated economies of scale would decline as well, driving up print per-title costs. Therefore, having modeled the outcome of a transition, wemust also consider these types of short-term effects that might accompany it, particularly scale effects.

Scale Effects

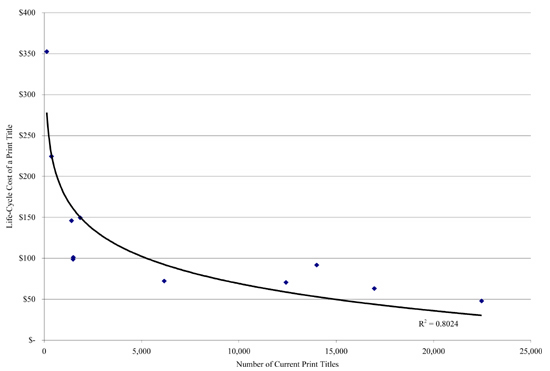

The presence of scale effects on the print format explains why the large libraries have a smaller cost differential than the smaller libraries.36 The evidence for economies of scale for the print format is clear (see figure 13). A larger operation requires less time per title than does a smaller operation, perhaps because processes can contain more specialization and routine. This is driven by manual tasks that vary principally by the number of subscriptions.37

Fig. 13. Relationship between the size and the life-cycle cost of the print collection

Fig. 14. Relationship between the size and the life-cycle cost of the electronic collection

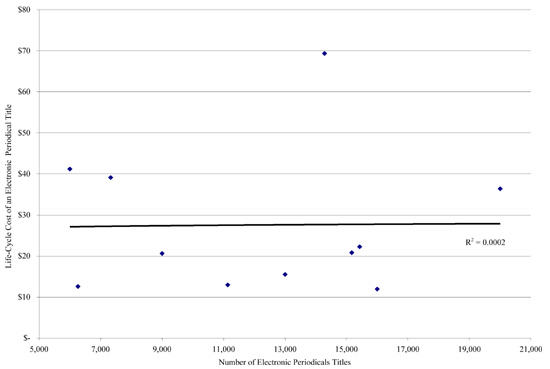

Equally striking is the absence of economies of scale in the electronic format (see figure 14). Several hypotheses for the lack of such a relationship may be advanced. First, the relative novelty of the electronic format suggests that the most efficient processes may not yet have been fully deployed. Further process improvements may yield scale effects. Another possibility is that the nonsubscription costs of electronic titles accessed as part of an aggregation may be far lower than those of titles accessed individually or as a small group from a publisher. (This finding was reported by Montgomery and King 2002.) The distribution of a library’s titles (i.e., a comparison of titles received from publishers versus large aggregators), might be a more revealing source of cost differential than scale effects themselves. The present study’s design did not call for the collection of data that might permit us to address this uncertainty, and it might constitute an area for further research by others.

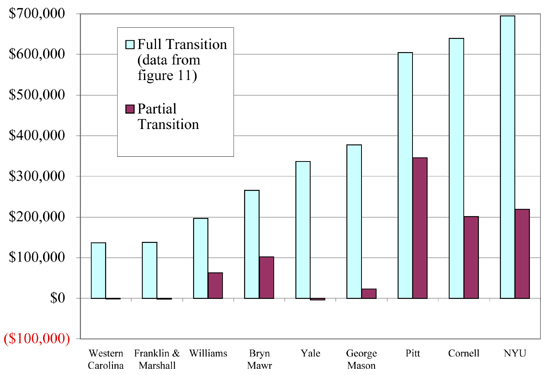

Recognizing the different economies of scale allows us to project the potential cost effects for a library that would make an immediate transition of, say, 50% of its collection, but not the entire collection. To make such a projection, we assume that each title transitioned achieves the same life-cycle cost as other electronic titles at that library do (since there are at present no scale effects on the electronic format), but that the cost per remaining print title will rise as a result of scale effects, as predicted by the curve in figure 13.38 We also assume the rates of print-electronic duplication that were discussed at figure 11. The outcome of this calculation, shown in figure 15, demonstrates starkly that a partial transition would, for many of the libraries, have notably different cost effects than would a full transition.

Fig. 15. One year after a 50% transition from print to electronic (total cost differential over 25-year life cycle)

Many of the libraries might still achieve savings, although all would see their savings eroded and some might even experience a net cost. The cost effects we have found to be associated with a partial transition, which are driven by the positive scale effects of the print format, deserve careful consideration by any library that is planning a strategy for the transition from print to electronic format. If a full transition is eventually to be achieved, the near-term transitional effects may of course be of only short-term importance. But it cannot be ignored that the transitional period, especially if it is a long one, will result in increased unit costs for print periodicals as the number of print titles is reduced. Many libraries are already along the path of such a partial transition. But the slow ripping of the bandage is always more painful. From this perspective, a faster transition would, other things equal, be preferable.39

Management Challenges

There are a number of other reasons why it might not be possible to recapture the total annual cost differentials discussed above. A significant amount of the cost differential that this study has documented is attributable to lower staff-time expenditures. Unlike savings that result from unbuilt space, which are difficult to reallocate,40 staff and student-worker time may be redirected or their positions reassigned. Because of the varying skill sets of individuals and the difficulty of reallocating relatively small amounts of employees’ time expenditures, it would probably be impossible to reallocate all the staff time expenditures in perfectly efficient ways. For example, it might be difficult to reassign 2% of a librarian’s time expenditures, especially if that person is a skilled cataloger who will not necessarily take on public-service tasks during the freed-up period of time. Realizing the full potential cost decreases would pose a significant management challenge.

Before we could conclude with any certainty that cost differentials on this scale could be expected, we would need to know whether the collection size of a given library will grow significantly during the transition from print to electronic and, if so, how. The evidence from several of the libraries in this study-in particular, the small and medium-size libraries-suggests that far more electronic titles are being received than was ever the case with print (see figure 1). If this phenomenon holds true, then some might be led to conclude that the lower unit costs may be offset, at least partially, by a higher total number of units. On the other hand, some say that many of these additional titles are not really wanted by the subscribing library, and some libraries are beginning to move back to access models that afford greater control over the specific titles that they license. If this trend continues, the vast increases in available titles might become far less of a factor than they now appear to be.

While our data clearly indicate that unit costs will decline, this section has suggested a number of reasons why local practices will determine the budgetary impact of any cost decreases. Where collection sizes do not increase significantly, and where efficient procedures and time reassignments can be implemented, a transition could be expected to have a salutary effect. We believe, on balance, that decreases in total nonsubscription costs present the most likely scenario for the future. Questions of implementation, however, remain to be addressed.

FOOTNOTES

35 For some survey-based findings on faculty tolerance of electronic periodicals, see Dillon and Hahn 2002; Guthrie 2001; Friedlander 2002; and Guthrie and Schonfeld 2004.

36 The consideration of scale effects in examining costs of libraries has a notable history, as outlined in Lin 2003. Our work is less complicated than many of the precedents discussed there, because we focused on a discrete portion of the academic library, rather than developing a library-wide cost function.

37 The scale effects attain a high level of statistical significance for the print format if measured on a per-subscription, rather than a per-title, basis, since certain activities (such as cataloging) are presumably more cost-effective when performed locally for multiple copies of a given title.

38 The equation for the curve is y = -48.005Ln(x) + 511.33.

39 Connaway and Lawrence (2003) reported librarians’ concerns about the burden that a transition period would place on their resources.

40 Reallocating the cost of unbuilt space is, economically, a sound concept. It is, however, a complex argument to make, except in cases where shelves are bursting at their seams and expansion is imminent. See Schonfeld 2003, 367-72.