Debra K. Andreadis, Christopher D. Barth, Lynn Scott Cochrane, and Karen E. Greever

Libraries, better than most institutions, have long understood the value of cooperation and collaboration. Since the role of a library is to make information freely available, to promote its use, and to preserve it so that it remains freely available, libraries can surely accomplish more working together than they can separately. Realizing the need to make the most of their cooperative and collaborative networks, Kenyon College and Denison University have begun reorganizing technical services across the two campuses through the creation of a joint department of collection services. Budget cuts and staff reductions were not factors in the decision to undertake this project; the goal was the colleges’ desire to do more-not with less, but with what they had. This step was a way to combine two great technical services teams and make better use of the expertise at both institutions to increase the efficiency of current services and add new ones. The lure and challenge of electronic information; the desire to provide greater access to local, specialized collections; and a desire to be proactive rather than reactive were at the core of this effort. It has led to more-empowered employees working collaboratively to provide the best-possible customized information access tools for their constituents.

The Context

Denison University and Kenyon College, two small, liberal arts schools located 27 miles apart, are members of the Five Colleges of Ohio consortium. The other three members of the consortium are Oberlin College, Ohio Wesleyan University, and the College of Wooster. Four of the schools (Denison, Kenyon, Ohio Wesleyan, and Wooster) have shared an online catalog, CONSORT, since 1996 and have participated in cooperative collection initiatives. The five college libraries share a leased storage facility, CONStor, and all are members of OhioLINK, a statewide consortium of 85 academic libraries including both public and private institutions and ranging from research universities to community colleges. A shared union catalog allows direct, patron-initiated borrowing from any participating institution in the state. Delivery is usually within five days. OhioLINK coordinates the purchase of more than 100 databases and more than 6,000 electronic journal titles. Members have participated in grant-funded initiatives for information literacy and for use of statewide digital media collections, and they are planning a statewide digital repository project.

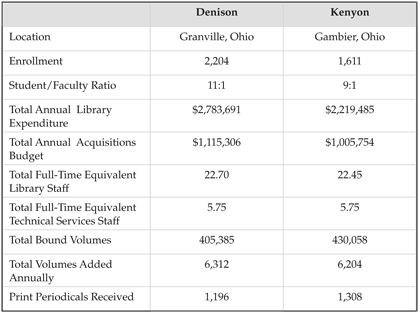

Because of their geographic proximity, Denison and Kenyon have long had a strong relationship of collaboration institution-wide, particularly between the two libraries. The two institutions have roughly comparable library collections, budgets, and staffing, which has also fostered close collaboration.

|

Table 1. Comparison of General Characteristics for Denison and Kenyon

Phase I: Project Planning

In the summer of 2003, a committee of three administrators, two technical services librarians, one public services librarian, one systems librarian, and one paraprofessional cataloger was formed to write a proposal to The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for a grant to plan the redesign of technical services work. Prior to writing the proposal, the committee had used Hammer and Champy (2001) as a catalyst for discussions on redesign. As part of the proposal-writing process, the group created a process map, a case for action, a vision statement, budget, and a time line (Five Colleges of Ohio 2003). To inform this process, committee members relied on many of the published works listed at the end of this chapter.

After receiving the Mellon grant in 2004, the group created a task force to do the actual planning and hired Maureen Sullivan as project consultant to provide general oversight and training in group dynamics. The goal of the project was to improve access to information resources and create value-added services for patrons through cooperative efforts. The task force agreed to the following assumptions and principles: (1) a workflow dealing with the majority of materials would be created and automated wherever possible; and (2) the goal would be to move materials between the two schools, and between each school and CONStor, in 24 hours or less.

The task force consisted of two librarians and two paraprofessionals from Denison, two librarians and three paraprofessionals from Kenyon, and the CONSORT systems manager. Five of these individuals had been members of the grant-writing committee. The library directors appointed a facilitator for the group. The task force met weekly. Its charge was to draft a written framework for how operations could be combined (or left independent), to identify the infrastructure necessary for plan implementation, and to consider how to position the unit to be as innovative and forward thinking as possible. Library directors from both schools participated in this group as needed; however, they had no role in planning the agenda and did not regularly attend meetings. The process was designed to be staff driven.

To launch its work, the task force held a retreat with the library directors and the project consultant in January 2004. The group reviewed its charge: to create a robust system for combined library technical services. The target was a system that would be flexible, transferable, malleable, and adaptable. Its focus would be evolving patron information needs, research patterns, and desires. Other discussions focused on work-redesign principles, planning assumptions, environmental assessment, vision, development of initial work redesign, agreement on how the task force would conduct its work, and a review of the project timeline.

A model for a consolidated department was built on the assumptions that it would

- be driven by user needs;

- have staff from Denison and Kenyon working a single unit to accomplish shared goals;

- build on the strengths of all staff members in the technical services areas;

- take advantage of technology to streamline work;

- create a combined collection that was greater than the individual collections;

- adjust to changes as necessary and be transferable;

- focus on systemwide processes; and

- hinge on staff participation and empowerment for success.

The project consultant facilitated a brainstorming session to generate additional ideas. R2 Consultants was hired to conduct an analysis of existing technical services workflows at both institutions. In April, R2 met with technical services staff as a group and then with each individual member. In May, all staff members were invited to attend the consultants’ presentation of their analysis and recommendations.

At this time, the task force prepared the following vision statement:

- Be courageous!

- Act as a collaborative unit to best serve users at multiple locations.

- Provide intellectual representation of the collection as a whole.

- Foster a culture of staff empowerment that effectively uses and rewards individual strengths.

- Enable research and development capacity for the entire organization.

- Appreciate that as processes are combined, some activities may still best be implemented separately.

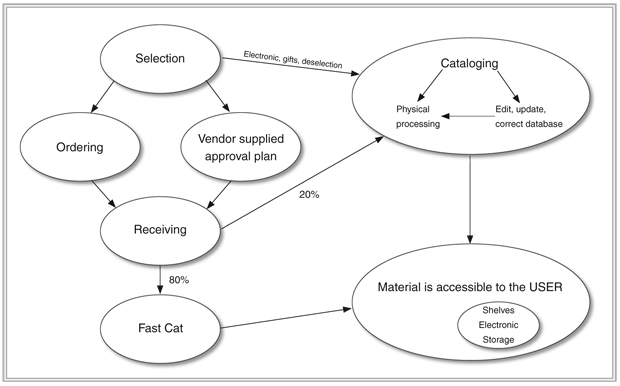

The group generated a work-process model (figure 1) and formulated a detailed plan based on the goals of the project (Library Technical Services Work Redesign Task Force 2004). It decided that the new technical services unit should be location independent and that the work process should be expandable. A joint-approval process that included cooperative selection, budgeting, and accounting would be created. Paper information flows should be replaced with electronic flows, and vendor services should be evaluated and integrated. These steps would allow the concentration of human capital in areas that could not be automated.

|

Fig. 1. Work Process Model

As shown in figure 1, the work process would have six components: (1) selecting (including the vendor-approval plan); (2) ordering; (3) receiving; (4) using Fast Cat for most of the print workflow; (5) cataloging; and (6) making materials accessible to users. These process definitions were deliberately broad and were intended to accommodate the diverse streams of materials currently processed as well as those that would be provided in the future. The process was designed to allow workflow to change to meet new circumstances.

Within the work processes would be four material streams: (1) print resources, including print periodicals and government documents; (2) electronic resources; (3) audiovisual resources; and (4) special projects. Using the same workflows, large percentages of each stream would be acquired, processed, and delivered to users. Applying efficiencies to all four streams would enable both libraries to dedicate more time to providing access to unique resources and services for our users.

Phase 2: Project Implementation

After nine months of effort, the task force delivered its plan to library directors and then to all staff at both libraries. Following dissemination and discussion, a three-person team was assembled in January 2005 to implement the plan. All members of the implementation team had been members of the planning task force. Included were a librarian from Denison, a paraprofessional from Kenyon, and the CONSORT systems manager. The team worked with staff at both institutions to define how the plan would work in real life, focusing first on print resources, especially monographs. After investigating logistical issues, the task force decided that technical services staff would initially continue at their current locations. In light of this decision, the team then determined the best way to change the processes so that neither school would be overburdened.

This work continued over the first half of 2005, and the first joint workflows were realized in late summer 2005. During the initial phase of joint operations, all purchasing, receiving, and cataloging of monographs from the primary book vendor for both institutions took place at Denison. Orders from other vendors and standing orders were processed at Kenyon. Materials were shipped daily between the two institutions. Vendors now provide more services, so as much material as possible is received shelf-ready. All materials received are spot-checked to ensure accuracy.

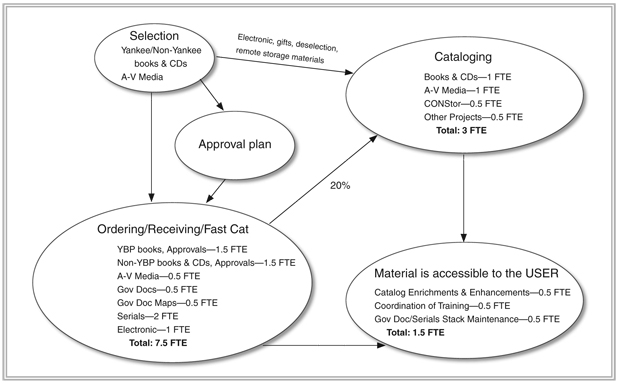

During the first phase of implementation, all staff members were provided a rough model of where full-time employees (FTEs) were to be deployed within the new unit (figure 2). Staff members were asked to select where they were most interested in being stationed, on the basis of their experience and desire for growth. All staff members were assigned to work in their respective areas of preference. As staff had previously been engaged largely with the work of their entire units, most expressed a desire to work in multiple areas under the new configuration. Efficiencies stemming from the combined workflow achieved a savings of 2.5 FTEs. The plan proposed that this surplus be redeployed within the unit to perform duties not previously performed, including cataloging of electronic resources (1 FTE), identification and implementation of strategic initiatives with regard to catalog enrichments and enhancements (1 FTE), and coordination of training initiatives for the unit (.5 FTE).

New work assignments are being more clearly defined as staff members begin to participate in new workflows. More complete position descriptions will be developed after workflows are settled and well understood. The human resources offices at both campuses have been kept informed about the project, and they support the changes in position descriptions and evaluation procedures that have been and will continue to be made. A new leader for the combined unit was hired in February 2006. This librarian reports to both campus library directors and carries forward the vision for integration within the unit.

|

Fig. 2. Revised Work Process Model

The next phase of implementation will be to create work teams across the two schools. Each member of the staff will be on two teams. One team will comprise all the members who work within the same process (within the same bubble on the model). A second team will comprise all the members who work with the same general media type. Currently, the media types have been designated as (1) books; (2) electronics, government documents, and periodicals; and (3) audiovisual materials. Once established, these teams will designate a team leader; this responsibility will rotate among members. The charge to teams is to work together to ensure that members communicate effectively, that they share ideas openly, and that they explore new ways of working cooperatively.

The combined unit will continue working to finish implementation across all media streams, particularly audiovisual materials, where there are significant differences between the campuses regarding how these media are handled. Many staff in the unit and in both libraries are also beginning to think critically about what it means to create a more useful library catalog with new access tools and have begun to generate creative proposals. These include catalog and catalog record enhancements, increased local use of metasearch tools, and coordinated digital collections initiatives.

Conclusions

The overriding lesson of this project was that the journey was just as important as the ultimate goal. The process of engagement was well worth the time, and the end product put the participants in a good position to work as innovators in their libraries, not just within management but throughout the ranks of all staff, thereby creating a critical connection to the libraries’ fundamental missions.

The following factors were critical to the success of the process and the product:

- clear, patient, collaborative leadership from the library director and dean, along with complete support from their superiors on campus;

- regular, transparent, and repetitive communication of the broad goals and implications of the work to be done, in recognition of the fact that it was necessary to think not only about the tasks to be done but also about broader workflows;

- a thorough, well-reasoned proposal before planning was begun;

- an experienced consultant to assist the project team with the difficult work of managing change;

- a consortium partner that shares an online catalog, delivery service, or storage facility, and preferably all three; and

- honesty about the motives for the project, especially if it entails saving money or eliminating positions.

The key to addressing all these issues was clear and ongoing communication that reflected the overall goal of the project. Communication was not always handled in the optimal way, but as work proceeded staff learned more and more how important it was to be as open as possible about where the libraries were headed and about the decisions being made. Once trust had been established, working through the inevitable hurdles became much easier. Communication centered on broad, and often theoretical, discussions about the library profession and about how libraries should be positioning themselves within the changing world of information providers. This helped everyone focus on the general implications of networked information for library work rather than on individual tasks. This communication strategy helped make the case for change, even when things seem to be working fine at the time.

Staff involvement and ownership were critical to moving the project forward. Task force members needed to spend a fair amount of time getting to know one another before they could communicate comfortably within the group. It was sometimes difficult for some members to speak their minds because of the mix of staff (including supervisors and those they supervised), but in the end the benefits were worth the effort. The mix of people allowed for different viewpoints to be expressed and incorporated into the final plan.

The time required to create this level of change was greater than anticipated. Every step of progress involved many modifications to the workflow, some of which were not foreseen. At times this was because of the number of staff and vendors involved in each decision. For instance, the decision to receive shelf-ready books from the major vendor involved input from technical services staff at each location, input from the vendor, a PromptCat profile change at OCLC, and budget approval. A slowdown at any point in this process increased the time needed to make the change a reality.

Any initiative designed to combine work units between institutions is not guaranteed of success, and the work was not always easy. Some of the challenges encountered and resolved together include :

- reaching consensus with partners who were not part of the project;

- overcoming resistance to change (“If it ain’t broke, why fix it?”);

- staffing a joint unit with employees who did not always want to work in a new location;

- getting everyone to let go of the “perfect” on behalf of the “good”; and

- learning to manage digital information and products in all formats, especially those that were locally produced.

Nevertheless, these were minor hurdles on the road to improved customer service. While the full implementation of the project lies ahead, the future looks promising.

References

Five Colleges of Ohio. 2003. Library Technical Services Work Redesign, Denison University, Kenyon College: Application to The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Available at http://www.denison.edu/collaborations/ohio5/libres/lwrtf/proposal.html.

Hammer, Michael, and James Champy. 2001. Reengineering the Corporation. New York: Harper Collins.

Library Technical Services Work Redesign Task Force. 2004. Plan for Library Technical Services Work Redesign, Oct. 2004. Available at http://www.denison.edu/collaborations/ohio5/libres/lwrtf/planning_report.pdf

For Further Reading

Bloss, Alex, and Don Lanier. 1997. The Library Department Head in the Context of Matrix Management and Reengineering. College & Research Libraries 58 (November): 499–508.

Boissonnas, Christian M. 1997. Managing Technical Services in a Changing Environment: The Cornell Experience. Library Resources & Technical Services 41 (April): 147–154.

Brewer, Joseph M., Sheril J. Hook, Janice Simmons-Welburn, and Karen Williams. 2004. Libraries Dealing with the Future Now. ARL 234 (June): 1–9. Available at http://www.arl.org/newslter/234/dealing.html.

Calhoun, Karen. 2003. Technology, Productivity and Change in Library Technical Services. Library Collections, Acquisitions, and Technical Services 27(3): 281–289.

De Rosa, Cathy, Lorcan Dempsey, and Alane Wilson. 2004. The 2003 OCLC Environmental Scan Pattern Recognition: A Report to the OCLC Membership. Dublin, Ohio: Online Computer Library Center.

Eden, Bradford Lee, ed. 2004. Innovative Redesign and Reorganization of Library Technical Services: Paths for the Future and Case Studies. Westport, Conn.: Libraries Unlimited.

Hayes, Jan, and Maureen Sullivan. 2002. Mapping the Process: Engaging Staff in Redesigning Work. Wheeling, Ill.: North Suburban Library System.

LeClair, Annette M. 2004. Centering Technical Services: Developing a Vision for Change at Union College. In Innovative Redesign and Reorganization of Library Technical Services Paths for the Future and Case Studies, edited by B. L. Eden. Westport, Conn.: Libraries Unlimited.

Lomker, Linda Haack. 2002. Nimble as Cats, Dependable as Dogs: Subject-Based Technical Services Teams and Acquisitions. Library Collections, Acquisitions, and Technical Services 26(4): 343–344.

Lopatin, Laurie. 2004. Review of the Literature: Technical Services Redesign and Reorganization. In Innovative Redesign and Reorganization of Library Technical Services Paths for the Future and Case Studies, edited by B. L. Eden. Westport, Conn.: Libraries Unlimited.

Mastraccio, Mary L. 2004. Quality Cataloging with Less: Alternative and Innovative Methods. In Innovative Redesign and Reorganization of Library Technical Services Paths for the Future and Case Studies, edited by B. L. Eden. Westport, Conn.: Libraries Unlimited.

McLaren, Mary. 2001. Team Structure: Establishment and Evolution within Technical Services at the University of Kentucky Libraries. Library Collections, Acquisitions, and Technical Services 25(4): 357–369.

Propas, Sharon W. (1997). Rearranging the Universe: Reengineering, Reinventing, and Recycling. Library Acquisitions 21(summer): 135–140.

—. Ongoing Changes in Stanford University Libraries Technical Services. 1995. Library Acquisitions 19 (winter): 431–433.

Snyder, Monteze M. 2001. Building Consensus: Conflict and Unity. Richmond, Ind.: Earlham Press.

Technical Services Redesign Archive. 2004. Stanford University Libraries (Last modified August 11, 2005). Available at http://www-sul.stanford.edu/depts/ts/about/redesign/.

Younger, Jennifer, and D. Kaye Gapen. 1990. Technical Services Organization: Where We Have Been and Where We are Going? In Innovative Redesign and Reorganization of Library Technical Services Paths for the Future and Case Studies, edited by B. L. Eden. Westport, Conn.: Libraries Unlimited.

Zuidema, Karen Huwald. 1999. Reengineering Technical Services Processes. Library Resources & Technical Services 43(1): 37–52.

Presentations

Andreadis, Debby, Chris Barth, and Scottie Cochrane. 2005. Collaborative Technical Services Work Redesign at Denison University and Kenyon College. Poster presented at the Association of College and Research Libraries National Conference, Minneapolis, Minnesota, April 7–10, 2005. Available at http://www.denison.edu/collaborations/ohio5/libres/lwrtf/poster_layout.ppt.

Cochrane, Lynn Scott. 2004. Denison University & Kenyon College Library Technical Services Work Redesign. Paper presented at the Charleston Conference, Charleston, South Carolina, November 2–5, 2004.

Conrad, Ellen, and Andrea Peakovic. 2005. Denison University and Kenyon College Library Technical Services Work Redesign. Paper presented at the 2005 Ohio Valley Group of Technical Services Librarians Conference, Newark, Ohio, May 11–13, 2005.

Cochrane, Lynn Scott. 2005. Denison University and Kenyon College Library Technical Services Work Redesign. American Library Association Annual Conference, Chicago, Illinois, June 24–30, 2005.