By Stephen Nichols

The Romance of the Rose was the most popular vernacular work in the Middle Ages. It was also one of the longest at some 21,000 lines of verse, or around 250 manuscript leaves (500 pages). That’s about as far from a 140 character tweet as one could imagine. But medieval readers had lots of time. And what more appealing than a story of a young poet’s adventures in the Garden of Love searching for the ideal woman, his “Rose?” Chaucer translated it, Dante read it, kings and queens owned illustrated copies of it. For 600 years it’s been printed in many languages. Now it’s about to meet what may be its greatest challenge: joining the expanding world of medieval “twitterature.”

That’s right, twitterature. It turns out that medieval literature is very popular in what a colleague aptly calls the “manic sphere of social media.” Famous figures have risen from the grave to tweet out to us: King Cnut, Eleanor of Aquitaine, Geoffrey Chaucer, John Lydgate can be followed @cantusrex, @LaReineAlienor, @LeVostreGC, @Monk_of_Bury. Others, like Beowulf, rely on enterprising scholars, like Eleanor Treharne, a Stanford English professor, to put their case. Treharne set out to capture the magic of the Anglo-Saxon epic in 100 tweets, reports Alexis Madrigal in The Atlantic (January 10, 2014).”She compressed Beowulf into 100 tweets as part of teaching her course on the many ‘existing and imagined manifestations’ of the work.” Besides the value of Treharne’s adaptation for her students, she also reached more than 12,000 viewers who found her site Beowulf in a Hundred Tweets : #Beow100.

As an adaptation of scholarship and pedagogy to social media, tweeting medieval works requires arduous preparation as well as creative talent. If a relatively short text like Beowulf poses such searching questions (in Treharne’s words) as “What constitutes Beowulf? What is the core and what do we understand by ‘Beowulf’?” imagine the difficulty of tackling a really long work like the Romance of the Rose? That’s the challenge that Tamsyn Rose-Steel, the CLIR/Mellon Medieval Data Curation Post-Doc at Johns Hopkins, took on when she conceived the Rose Twitter project (@RoseDigLib #RoseRom).”In tweeting a piece of literature,” she says, “a number of parameters must be decided: should one keep the original wording and language or update it for a modern audience? Should the limitations of 140 character segments dictate the overall length? Indeed, why are we even doing this, and for whom?”

Paradoxically, Rose-Steel’s criteria for tweeting remind us that in its own time medieval literature constantly underwent the kind of updating and revision twitterature demands.In a pre-print world, each exemplar of a work was hand-copied and thus unique. In effect, a manuscript is a distinct performance, what we refer to as a remediated version. Not surprisingly, when scribes, artists, and decorators produced a manuscript, it often looked and read differently from other versions. True, these versions did not involve the drastic compression required of tweets, but, like twitterature, manuscript versions did update presentations to please their audience. Medieval book production was ever mindful of public taste and expectations, which probably encompassed a broader social range than today. Manuscripts created for royal, aristocratic, and high ecclesiastical patrons, for example, are quite different from the simpler, less lavishly illuminated copies of the same work produced for merchants, scholars, or minor clergy unable to afford the expense of costly colors for miniature paintings and historiated initials, expensive ink, fine parchment, and the elegant script of a first-class scribe and rubricator.

But, Rose-Steel noted other similarities between Twitter and medieval literature, as she planned the project. If social media is the unregulated transfer of information, that’s not so different from the oral literary tradition that underlay medieval literature. How else conceive of the spontaneity with which scribes could interpolate their own thoughts in a narrative, or in their marginal commentaries (glosses) if not as in the same spirit of unregulated information transfer we find on Twitter and other social media? Beyond these technical similarities lies a more important constant linking Twitter and medieval literature. The latter lived by continual human intervention and embodiment.No two manuscript versions of a medieval poem are alike because of intense human interaction with the language, narrative, and artistic visualization on parchment folios by the scribes and artists who “performed” it. It was that renewal, that dynamic reimagining of a work that medieval audiences responded to and that maintained it as a living object.

And that’s exactly what poet Michael Rose-Steel and medievalist Tamsyn Rose-Steel have undertaken in transposing the Middle French Roman de la Rose into contemporary tweets. Mike sees his reworking of the Rose as continuous with his own verse. “My poetry gravitates towards formal constraint (especially numeric limitations) and ekphrasis,” he observes. “The Rose project automatically provides this framework; the verbal compression and temporal segmentation required by Twitter’s short, drip-feed delivery forces me to consider several qualities that would be muted by a single poem on a page, or an interactive installation.” He goes on to elaborate. “It requires a three-fold challenge:

- to adapt to the tweeting format, so that each tweet can be equally understood on its own and as part of the greater whole, which will be available only after the event, some six months after the first transmission;

- to explore the possibilities of conveying in modern style and vocabulary a medieval narrative—remaining true to the source while also revealing something about its reception today;

- to produce poetry within these constraints that is interesting in its own terms, not merely a pastiche or a novel means of communicating. This is simultaneously a question about the boundaries between translation and creation, and where this project will situate itself.”

Tamsyn notes that a work of this length poses the urgent problem of how to divide up the text. Since this project did not aspire to be yet another of the many available translations of the Rose, line-by-line tweets were rejected from the outset “because this approach would leave little room for poetic invention.” A more interesting approach, they felt, “would be to match each tweet, or tweet-combo, with a thematic unit of the text.” In keeping with the focus on the essence of narrative themes, they “retained the octosyllabic form (with a little looseness to fit the tendency of English to mumble in places) and to combine mostly half-rhyme with some full rhymes and occasional blank couplets.”Such an approach gives scope to English prosody, while at the same time retaining some features and flavor of the original. They sensed rightly that too close an adherence to the regular octosyllabic, rhymed couplet mode of the Middle French original would sound archaic and strained. It would miss the supple, dynamic essence of the original that English verse at its best can capture. And that’s just what Tamsyn and Mike Rose-Steel have succeeded in doing.

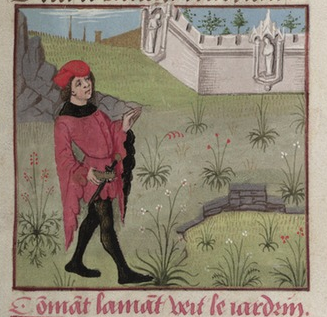

To give a sense of their achievement, I’ll conclude with several examples from the first thematic unit: The Garden of Pleasure. Let me first quote three tweets that launch the narrative, then several that introduce the ekphrastic images the lover sees painted on the exterior of the wall of the Garden of Pleasure. These images portray human states incompatible with love.

- One night, my sleep was speared

by such a telling dream; it seemed

that Love had summoned me to see,

as he so often does a youth of twenty

*****

I’ll tell you all about it. I propose

to call it the Romance of the Rose,

and dedicate it to the one who truly

understands: my own Rose, my Lady.

*****

May is nature’s fashion week,

a spiraling collection of greens and leaves

struts everywhere. My dream was spring

and full of song.

2. I came upon a garden with high walls,

decorated with images as I recall:

*****

Hate, raged in the center, scowling,

her beastly body wrapped in toweling.

Even so small a sampling suggests the vigor of the poetic re-imagining of the Romance of the Rose that Mike and Tamsyn Rose-Steel are realizing, one tweet at a time. The more than 2,000 viewers who follow, favorite, and retweet their posts confirm that people like what they see. I know, because I’m one of them [@sgn_58].

Stephen G. Nichols is James M. Beall Professor Emeritus of French and Humanities at the Johns Hopkins University, and CLIR Distinguished Presidential Fellow.