By Timothy Norris

As a newcomer to the world of libraries and information science with training in ecology and geography, I struggle with the metaphor of “information ecosystem” that is enthusiastically used to describe human-built information systems. I expressed this concern at the recent CLIR bootcamp for the 2014-16 fellows and was pleased to find that it started a lively discussion, but in the end no clear explanation of the metaphor was articulated. This blog explores my difficulties and voices a warning against the use and/or abuse of ecological concepts in information science.

At first my difficulty lay in identifying the intended meaning of the metaphor. Is the speaker talking about diversity? If so, the diversity of human actors, the diversity of information, the diversity of institutional actors, or what? Is there a sustainability component? If so, which resource is a limiting factor: the supply of energy, a material thing like spinning disks, or some required “nutrient” like financial resources? Are we talking about emergent behavior in complex systems akin to artificial intelligence arising from linked data? Holism? Is the reference to complex and dynamic equilibriums somehow governed by the ever-shifting interpretations of intellectual property law? Are there predator-prey relationships, such as those between publishers and authors? Is there competition in populations, be they groups of authors, academic institutions, or commercial publishing enterprises? Or are there growing and thriving communities built on shared needs?

And the list goes on.

It seemed that the metaphor was understood in a variety of ways by both speakers and audiences. Often the meaning was a jumbled cacophony of the concepts listed above with a few more thrown in for good measure. Even more frustrating is that “information ecosystem” appears mostly in titles (of articles, books, and events) or in abstracts and introductions, but is never well explained. I cannot find one definition for “information ecosystem,” not even in the OED (although Wikipedia does have an information ecology entry). Apparently the metaphor is simple and straightforward and only an ecologist might struggle to understand its use. The “information ecosystem” buzzes and makes everyone feel good. Yes!

Let us take a step back.

It was in 1935 that the British ecologist Arthur Tansley coined the term ecosystem in his seminal article “The Use and Abuse of Vegetational Concepts and Terms.”[1] His main concern was that fellow ecologists were referring to ecosystems as organisms; the ages-old organismic metaphor, much like Lovelock’s Gaia Hypothesis, that is used to explain both natural and social phenomena. Tansley was building upon the German biologist Ernst Haeckel’s 1866 conception of “ökologie,” which in turn built upon studies of natural history that can be traced back to Ancient Greece. While the word ecology is literally translated as the “study of the house,” most practicing ecologists understand it as the study of the interactions between living organisms and their material environment; the ecosystem itself cannot be an organism.

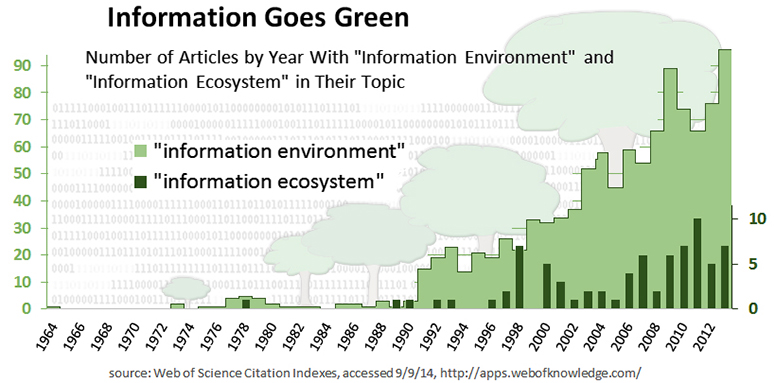

With the advent of digital computers in WWII and the subsequent interest in the management of larger and larger sets of information, people began to speak of the “information environment.” This term is still used to describe the hardware, the software, the human specialists and the institutional contexts that comprise the information systems of large business corporations and other enterprises that manage big data. Terms such as “knowledge ecosystem” and “digital ecosystem” also emerged (from Europe?) and within the last decade professional conferences on the “Management and Computational and Collective Intelligence in Digital Ecosystems” or the “Digital Ecosystems and Technology Conference” have been inaugurated. As would be expected, these conferences are run by experts in business logistics and computer science. Apparently no ecologists are present.

It was more recently, in the late 1990s, that the terms “information ecosystem” and “information ecology” started to gain currency. Again, the metaphor seems to have been initiated by specialists in business process innovation and knowledge management, but others have since adopted it. In 2003 the Duke Law School launched the Information Ecology series of lectures. The interdisciplinary conversation focused on intellectual property law, the public domain, and the dynamic information systems of the fast-growing worldwide web. The MIT Media Lab now has a working group with the title Information Ecology. Their focus is on how information gathered from our devices can be used to “to more smoothly mediate the boundaries between the physical and information worlds we inhabit.” And as noted previously, the metaphor is enthusiastically used in the realm of digital librarianship.

Without doubt, thinking of information systems as an ecosystem can be useful. Our information systems are complex, diverse, interconnected, collaborative and competitive, evolving and adapting, and exist in a state of dynamic equilibrium. We can also say that within these information environments there are predators and prey, functional groups of actors (researchers, developers, vendors, practitioners, and so on), niches, issues of sustainability, and characteristics of fragility. Even more interesting is recent interdisciplinary work on sustainability undertaken by several lawyers and economists that draws connections between copyright law, natural resource management, and the shared tensions between private and common property in both the material world and the intellectual domain.[2] The idea of a sustainable information ecosystem is intriguing indeed, but what is being sustained, for who, and at what price?

Apparently my dilemma with the metaphor as a trained ecologist makes me an outsider in the professional information world. So I struggled for several weeks with my squeamish feelings about the ecological metaphor and then I found solace. Within certain critical academic circles naturalizing a phenomena that is a human creation—somehow perceiving the social phenomena as natural—is considered dangerous. A good example might be an explanation of the conquest of Peru as inevitable and “natural” because of superior European weaponry and the disease trajectory from Europe to South America (to simplify a famous argument). Nowhere in this explanation is it mentioned that the conquistadores were social outcasts with a tendency for violence and disrespect of life; perhaps another factor in the conquest.

The solace that I found with my discomfort for the ecological metaphor in information systems came from the words of Richard Stallman, who launched the free software movement. “It is inadvisable to describe the free software community, or any human community, as an ‘ecosystem,’ because that word implies the absence of ethical judgment.” Stallman continues:

The term “ecosystem” implicitly suggests an attitude of nonjudgmental observation: don’t ask how [sic] what should happen, just study and understand what does happen. In an ecosystem, some organisms consume other organisms. In ecology, we do not ask whether it is right for an owl to eat a mouse or for a mouse to eat a seed, we only observe that they do so. Species’ populations grow or shrink according to the conditions; this is neither right nor wrong, merely an ecological phenomenon, even if it goes so far as the extinction of a species.

By contrast, beings that adopt an ethical stance towards their surroundings can decide to preserve things that, without their intervention, might vanish—such as civil society, democracy, human rights, peace, public health, a stable climate, clean air and water, endangered species, traditional arts…and computer users’ freedom.

Perhaps these words also apply to information systems—as these systems are indeed social phenomena—and although the ecosystem metaphor may be convenient and perhaps even practical, we should be careful with expressing an implicit lack of morality in the world of information.

Timothy Norris is a CLIR Postdoctoral Fellow in Data Curation at the University of Miami Libraries.

[1] Tansley, A. G. (1935). The Use and Abuse of Vegetational Concepts and Terms. Ecology 16(3): 284-307.

[2] See the 2003 special issue of Law and Contemporary Problems on “The Public Domain” as a starting point.