This is the third post in a five-part series called “Five Years of Listening” on the evolution of the Digitizing Hidden Collections program.

—By Nicole Kang Ferraiolo

“What I don’t understand is where did all the money go? We were partners on a grant of more than a million dollars and we saw none of it.” Many of the community-based archivists present nodded in understanding. I turned to the group and asked, “How many of you have actually seen a budget for a grant you partnered on?” I didn’t register a single affirmative response.

This scene took place last September in New Orleans at the Architecting Sustainable Futures symposium, a remarkable meeting focused on the long-term financial sustainability of community-based archives, funded by the Mellon Foundation and organized by Shift. While much of what I’d heard there was inspiring, this conversation was alarming to say the least. Perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised; the issue of inequitable partnerships is not new to funding organizations. At CLIR, collaboration has been a key tenet of both the Digitizing Hidden Collections grant program and the cataloging program that preceded it, and both initiatives have grappled with its intrinsic challenges. For this reason, CLIR’s independent review panels have paid close attention to the nature of proposed partnerships when determining awards. All collaborative projects funded through our programs should be founded on mutually beneficial, meaningful relationships. And for those of us on staff, many of the inspiring partnerships we’ve supported continue to be a source of pride.

There are significant reasons for incentivising collaboration, including the potential for increased efficiency, sustainability, and risk mitigation. Most importantly, collaboration has been a way to make our program available to new types of applicants, particularly those with less experience applying to competitive national grant programs. Through collaboration, a smaller institution might get access to experts that they can’t afford to keep on staff, such as specialists in digital preservation or intellectual property. It has been a way to level the playing field, and for better-resourced institutions to share the wealth. By many measures, incentivising collaboration has worked. We’ve been able to grow the number of institutions funded through the program: whereas the number of funded projects to date is 66, we’ve funded 160 unique institutions. Perhaps even more heartening is the increasing strong belief by individuals in our applicant community—including many in leadership positions at wealthy institutions—that inter-organizational resource sharing is a moral imperative.

Yet inequitable partnerships continue to persist. Back in New Orleans, I learned that a number of the community-based archivists present had been asked to partner on applications for Digitizing Hidden Collections, but hadn’t been invited to collaborate on any component of the draft proposals, including the budgets. In most of these cases, the partnering institutions did not receive a copy of our application guidelines, so our policies were communicated through the lead applicant, like a game of telephone. One archivist had heard incorrectly that CLIR required the lead institution to be a university, and was surprised to learn that the smaller partner could be the primary applicant, or could apply independently. And although the lead institution acts as the fiscal agent for grant funds, we don’t require that the lead institution receive a greater share of project funds than the collaborating partners; this too was news to many in the group. Miscommunications and unbalanced project design are not unique to Hidden Collections. I recently served on an external review committee for another funding organization and in the applications I read, much of the expertise and even the labor for the proposed projects was coming from lean community memory organizations, yet compensation for these institutions or the individuals that staffed them often amounted to less than 3% of the total project budget.

This year, Digitizing Hidden Collections made equitable partnerships a priority and we’ve adjusted our most recent guidelines to address this issue directly. Now all applicants proposing a collaborative project must confirm that representatives from all partner institutions have received: a) access to the program guidelines, b) an opportunity to participate in the project design process, and c) a copy of all final application materials. While we are operating largely on the honor system, we have asked applicants to include contact information for the primary representative at each collaborating institution and reserve the right to share the submitted application and reviewer feedback with the named individuals, and to include them on relevant correspondence. Meanwhile, we’ve added a prompt for collaborative projects to our budget narrative that asks how the proposed distribution of funds will encourage an equitable partnership. Applicants must explain their rationale in cases where a significantly greater portion of the funds will go to just one (or a small number) of the participating institutions. We will continue seeking to improve our guidelines in future cycles; for instance, we’re currently reflecting on how our policy that requires Canadian institutions to partner with a US lead affects power dynamics within those relationships. For now, we hope that our recent changes will inspire applicants to think more deliberately about the nature of their collaborations and will help increase transparency between partners.

Community and community-based archives are having a moment right now, particularly in funding circles. To me, this is thrilling and promises a much-needed diversification of the historical record and the people who preserve it, but it also adds new urgency to the issue of inequitable partnerships. Power imbalances between an institution with a large endowment and an independent archive running on volunteer labor are inherent and often rooted in much deeper histories and social tensions; some have argued that truly equitable partnerships in this context aren’t even possible. Funders clearly can’t solve this alone; the issue is bigger than us. And yet, it’s on us to acknowledge that we shoulder some responsibility for the imbalances present in grant proposals and can use the tools at our disposal to promote partnerships that are more equitable. At this point, it’s no longer enough to ask for greater collaboration, we must push for better collaboration.

If you have feedback or ideas to share about Digitizing Hidden Collections and/or Recordings at Risk, or general thoughts for CLIR’s grantmaking team, you can submit them here or write to hiddencollections@clir.org or recordingsatrisk@clir.org.

The Digitizing Hidden Special Collections and Archives program is made possible by funding from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

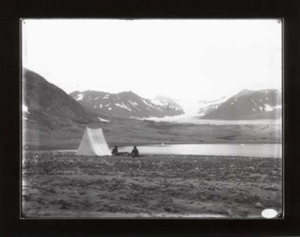

Harry Fielding Reid. 1892 Charpentier Glacier: From the Glacier Photograph Collection. Boulder, Colorado, USA: National Snow and Ice Data Center/World Data Center for Glaciology. Image from University of Colorado’s “Revealing Our Melting Past: Toward a Digital Library of Historic Glacier Photography” project, funded by a 2015 Digitizing Hidden Collections grant.

Read other posts in the series:

- Five Years of Listening, Jan. 31, 2019

- Digitization and the Dream of Openness, Feb. 7, 2019

- More Equitable Partnerships in Grant Funding, Feb. 21, 2019

- Toward a More Inclusive Grant Program, Mar. 12, 2019

- Still Listening, April 11, 2019