—Marlena Cravens

With the wildfire spread of COVID-19, many archives have closed in a bid to protect their employees and to decrease the rates of infection. These closures have left researchers caught between the desperate need to finish their projects and the need to return home to slow the spread of the virus. In the aftermath, many scholars took to #academictwitter to discuss ways to still be productive in quarantine without access to primary source materials. One of the most popular solutions posed has been increased archival digitization in the future, after COVID-19. To me, these discussions have been both fruitful and thought-provoking in new ways.

With the support of a CLIR/Library of Congress Mellon Fellowship, I began to work with the Preservation Research and Testing Division (PRTD) at the Library of Congress in the fall of 2019. Throughout the course of my work measuring early modern book wear and use, I’ve learned that digitization doesn’t just support conservation practices, increase access, or shield us from exposure to contagious diseases by keeping us at home: it could also protect us from the collections themselves. COVID-19 and the pigments I will discuss are not related and are not being equated, but the protocols that we use to protect ourselves are useful for nuancing how we interact with archival materials.

Dirty Books and Unknown Pigments

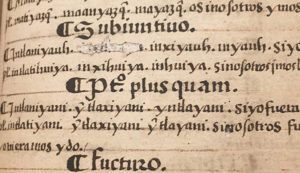

“It’s a really good idea to wash your hands after we finish up with this book,” Amanda Satorius mentioned as an aside. She was lining up a Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer against a small book the size of my hand. The humble, stained volume was Alonso de Molina’s Arte de la lengua mexicana y castellana (1571), a book intended to help Spanish priests learn Nahuatl grammar so that they could

communicate with different Aztec communities. We had taken the book out of Special Collections and brought it to the lab because of some strange white splotches on some of the pages. These stark white circles sometimes looked like they had been dropped accidentally onto the page by a hasty scribe. In other instances, they looked like they had been deliberately applied to cover up certain words. This careful censorship had been of interest to me. “These dots, for instance,” Amanda pointed to the more intentionally applied shapes. “It’s possible this is lead white. We won’t know more until I look at the results, but it’s possible.”

In a separate incident, my PRTD mentors—Meghan Wilson, Tana Villafana, and Amanda—and I stood in a circle in the lab and examined another innocuous, slim volume: Antonio de Nebrija’s Introductiones latinae. As a wildly popular book that saw numerous reprintings, many Early Modern students had used it to learn Latin. The edges of each page had been painted with a lovely bright red ink. The book had been printed just a little after 1492, and there was a very small chance that the red ink was made with cochineal from Mexico. There was a higher chance that it was vermillion, a bright red ink made from cinnabar. This type of red would contain mercury. Meghan immediately noted, “That doesn’t really look like cochineal.” Tana agreed, and she whisked it into her lab to use Fiber Optics Reflectance Spectroscopy (FORS) to find out if it was vermillion. As we all looked at our hands in concern, Amanda noted, “Make sure you don’t touch your faces. And definitely wash your hands before lunch.” Nobody disagreed.

These exchanges regarding the old spills and pigments in books always shocked me no matter how frequent and commonplace they turned out to be, and it has continued to preoccupy me throughout my tenure at the Library of Congress: one book contained a toxic pigment and the other might, pending the results. Other pigments can contain cadmium (yellow) or even arsenic (green). And yet, in our ignorance, researchers and archivists often handle old books and other materials without the appropriate care.

This isn’t a call to restrict book access when there are metal-based pigments. With good practices, these books are harmless, and most researchers do not interact with materials enough for this to be a concern. Rather, this is a reflection that this pandemic can teach us to be more thoughtful about how we interact with materials.We are trained to always handle collections with clean, dry hands and to avoid wearing gloves, which actually increases the risk of damaging fragile pages. We are also advised to avoid touching the ink and any other illuminations in a text, as this contact will degrade them. We all follow this protocol to the best of our abilities, and archivists in reading rooms often monitor to make sure that this is the case. And yet, there are bad practices that are harder to limit.

It is common to see a researcher resting their chin in the palm of their hand, rubbing the bridge of their nose, or tapping their pencil to their lips as they work through archival documents. This could expose researchers to the pigments that I listed. Researchers also might wash their hands coming out of the archives, as many old books are quite literally dirty, but this casual rinse of the fingertips belies the fact that they may not be aware of the nature of some of the pigments they have interacted with.

COVID-19 and Digitization

Archives, researchers, and archivists often can’t know if they’ve handled something with lead or mercury on it because of limitations in access to testing resources such as FTIR and FORS spectrometers. It simply isn’t common to have these machines on hand. As COVID-19 has now limited access to archives and has inspired us to take care washing our hands and avoiding touching our faces, these same protocols could protect researchers, archivists, and other stewards that study and preserve historic materials. The push to digitize more in the wake of COVID-19 could also offer a unique solution: protecting those who interact with these objects—both researchers and archivists alike—while also providing access.

Author’s Acknowledgements

My thanks goes to Amanda Satorius, Tana Villafana, Meghan Wilson, and Dr. Fenella France at the PRTD for their invaluable support. It also goes to Michael North and Dr. Stephanie Stillo in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress.

Marlena Cravens is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Texas at Austin and a CLIR/Library of Congress Fellow. The fellowship is awarded annually among CLIR’s Mellon Fellowships for Dissertation Research in Original Sources.

Editor’s note: This is the second piece in COVID (Re)Collections, a new series exploring responses to the COVID-19 pandemic by library, cultural heritage, and information professionals. Stories are proposed by the authors/contributors and reflect their personal experiences and perspectives at the time of submission. Learn more about the series and share your own story here.