A survey “by metes and bounds” is a highly descriptive delineation of a plot of land that relies on natural landmarks, such as trees, bodies of water, and large stones, and often-crude measurements of distance and direction. This was accepted practice before more precise instruments and methods were developed—indeed, the original 13 U.S. states were laid out by metes and bounds. More accurate means of measuring were established to overcome the method’s serious shortcomings: streambeds move over time, witness trees are struck by lightning, compass needles do not point true north, and measuring chains and surveyor strides can be of slightly differing lengths. However, the metes and bounds system is still used when it is impossible or impractical to make more precise measurements.

In undertaking our survey of the e-journal archiving landscape, we found that precise measurements and controlled data collection were not always possible. The e-publishing terrain is changing at time-lapse photography speed. Definitions and terms are widely interpreted, and standards are not yet established. These factors, along with our need to rely heavily on self-reporting by the programs, mean that direct comparisons between them may not always be valid. Despite this, we describe in this report the current lay of the land for scholarly e-journal archiving.

This study focuses on the “who, what, when, where, why, and how” of significant archiving programs operated by not-for-profit organizations in the domain of peer-reviewed journal literature published in digital form. Not included are preservation efforts covering digitized versions of print journals, such as JSTOR; library-led digital conversion projects; self-archiving efforts by publishers; and initiatives still being planned.

In preparing this report, our team focused on the following:

- soliciting library directors’ concerns and perceptions about e-journals;

- compiling responses from e-journal archiving initiatives taken from written surveys and semistructured interviews; and

- analyzing the issues and current state of practice in e-journal archiving, and forming recommendations for the future.

Library Directors’ Concerns

We began the study by developing a list of what library decision makers are likely to consider as they assess preservation strategies for e-archiving. The list was informed by our own research, discussions with colleagues, and comments made to staff members of the Center for Research Libraries (CRL) by member library directors.7

During March and April 2006, 15 North American library directors, representing a range of public and private institutions of various sizes as well as consortia, participated in telephone interviews designed to solicit their views on six key areas:

- Library motivation (Why should we be concerned about or invest in this?)

- Content coverage (Are current approaches covering the subject areas, titles, and journal components in which we are most interested?)

- Access (What will we gain access to? When and under what conditions?)

- Program viability (What evidence is there that these efforts are sufficiently well-governed and financed to last?)

- Library responsibilities and resource requirements (What will this cost our library in staff time, expertise, financial commitment? Would our support save the library money?)

- Technical approach (How do we judge whether the approach is rigorous enough to meet its archiving objectives?)

The interviews helped refine the issues to be covered in our survey. They also revealed some interesting opinions on the topic. Three common themes emerged in the interviews: the sense of urgency, resource commitment and competing priorities, and the need for collective response.

Sense of Urgency

These directors were all aware of digital preservation as a major concern, but they differed on whether it was a priority for support and action. Some felt the sense of urgency as a vague concern rather than as an immediate crisis, and several were willing to defer action until a crisis point is reached. Digital preservation is a “just-in-case scenario,” commented one director, “and this is very much a just-in-time operation.” Another noted, “Archiving is the last thing that gets taken care of because it’s the farthest thing out.” One director did assert that she would not want to gamble on what it would take to obtain access later if her institution did not invest now, likening that decision to not buying a book and waiting three years to see whether there was a demand for it. Several directors who have committed to supporting e-journal archiving do so because they have experienced loss. One acknowledged that her institution’s willingness to support digital archiving stemmed from the losses caused by a devastating flood: “Natural disasters make people focus.” Another director indicated that 9/11 raised his level of concern: “Prior to that, I had scoffed at the idea that the Internet would break down and I wouldn’t have access to my journals restored in 24 hours.”

One-third of the directors expressed more concern about the preservation of digital content other than e-journals. Virtually all expressed a lack of trust in publishers providing the solution, but many argued that publishers had to take on more responsibility. They pointed to efforts to include archiving clauses in licensing agreements. One questioned why she should have to pay additionally to support e-archiving initiatives: “We’ve pressured publishers to include archiving, and now we’re giving up on this?” Several pointed to the role that some publishers were already undertaking in collaborating with libraries to share preservation responsibility. One suggested that as the number of publishers decreases because of mergers and acquisitions, those remaining are making money and are not as apt to go under in the short term. Can an effective case be made, some asked, without there being an actual disaster? Another wondered about the future of licensed content in general for reasons other than digital preservation: “If you can’t get [e-journals] on the open public Internet, do they have much value anymore?” Several identified university records, Web sites, and digital content produced within institutions as more immediate concerns and were committing resources to their protection. “How do we sustain our role as the university archives in the digital age?” one asked.

Interviewees from some of the larger ARL libraries expressed the most concern about preserving e-journals. Although they argued that publishers had to bear some responsibility for e-journal archiving, they do not necessarily trust them to do this over time. One put it bluntly: “We definitely can’t wait this one out. I have a bias toward action and want to be involved. Until you explore it, you really don’t know what’s going on.” This concern was compounded by a sense of frustration over the options available. Understanding the issues is not the real problem, one noted: a lack of clarity about the solutions is. To date, few have committed real resources to address e-journal archiving, in part because they are unclear about what needs to be done. All directors interviewed acknowledged that a perfect solution is still many years away, and those who were willing to commit resources now stated their goal was to support a “good enough” solution that would be viable until the desired solution came along. One director characterized the decision of whether to commit resources as particularly acute for medium-size libraries. “The large ones will do it and worry about whether they should be doing this for others,” she argued, “and the smaller ones will say they don’t have the money. The ones in the middle with some resources and some sense of obligation are the fence sitters.” A director of an Oberlin Group library argued that leading liberal arts colleges would want to be involved as well.

Of the fifteen directors interviewed for this study, nine have committed or are prepared to commit resources to e-journal archiving, two are not, and four characterize themselves as fence sitters. The two who have decided to do nothing view their positions as managing risks and making hard decisions. Of the four who are undecided, one called himself a fence sitter only because he has not made up his mind about which initiative to support. Another characterized her institution as an “early follower, sitting on a fence by design, not because we wound up on one,” and a third concluded at the end of our discussion “I’m starting to think as we talk that sitting on the fence isn’t helping.” When asked what would provide additional incentives for getting off the fence, several pointed to peer pressure and reaching the “tipping point” of enough institutions participating. One said that he wanted to know where the major ARL libraries were going to put their money and why. One cited the importance of pressure from funding agencies such as The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation or their professional organizations. Another said that she would decide to do something in response to pressure from the administration or faculty members. Another indicated that having transparency in what is being done would be important, as was whether her institution would have a say in future directions. Several wanted to know about the circumstances and effort involved in committing to e-journal archiving, and how long they would have to wait before their institutions could restore access to their users following loss of normal access channels. Others wanted to know the costs involved, including staff effort, and what they would get from their commitment. They wanted to support those whom they could trust the most, whom they would have to pay the least, and who covered the material they care most about. Incentives to be an early subscriber were a big carrot. Knowing the penalties for waiting to join later was a potential big stick.

Resource Commitment and Competing Priorities

A recurring concern among the library directors interviewed was finding resources to commit to e-journal archiving programs. They pointed to competing priorities and the difficulty of identifying ongoing funds to support the effort.8 Many felt that while they might be able to provide resources for the next several years, support would eventually have to be found at the university or college level. Some were concerned that senior administrators would agree that the problem was real and that the library should address it, but that it would be difficult to get additional support. Digital archiving, one noted, is a new kind of expense, which is more difficult to argue for than increases to an existing expense. The directors requested sound bites to use with their provosts, presidents, and chancellors. (One mused that real horror stories would be better.) Several focused on the need to have faculty identify digital preservation as a major concern that directly affects them.

Almost all the directors rejected the argument that the savings in moving to electronic-only could cover the archiving costs. For most of them, that shift has already occurred as a result of lean budget years and dramatic increases in serials subscriptions, and the savings have already been reallocated to other purposes. “We couldn’t wait for the safety net to cancel,” said one. A director from the East Coast noted that many competing demands from new initiatives require ongoing financial support.

The greatest competition, however, lies in providing ongoing access to electronic resources. When a choice has to be made between the two, “broad and deep access at this point trumps more restricted access but a reliable archive,” concluded one director. “I’d rather buy more titles now than pay for something I might never use,” said another. Several directors from state institutions worried about justifying the use of state funds to purchase something “intangible” and questioned whether e-journal archiving could substitute for risk management measures locally. Others expressed more concern about guaranteeing perpetual access to e-journals than archiving them. One pointed out that his main worry was ensuring future access to content “below the trigger threshold” that would not be addressed by e-journal archiving. Another director questioned whether it was counter to his responsibilities to try to “preserve all e-journals when I can’t even get access to many of them because I can’t afford it.” Another commented, “It all comes down to money: present money versus future money.” One even suggested that it would almost seem like throwing money away: “You don’t have anything to show for it, and I’m not even sure that the solution would survive when you do need it.”

Need for Collective Response

All the directors interviewed rejected the notion of creating their own institutional solution. A major finding of the seven e-journal archiving projects supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation in 2001 was the difficulty of developing an institution-specific solution. At the end of that project, the Mellon Foundation decided to provide startup funds for both Portico and the LOCKSS Alliance (Bowen 2005). Several directors called for the creation of a national cooperative venture, saying, “We want to throw our lot in with other libraries.” Some wanted to tie e-journal archiving to their consortial buying and licensing efforts. Others felt that publishers had to be at the table as well, noting that libraries are too prone to seek internal solutions. One mused that libraries can now do with e-journal archiving what they have wanted to do for 40 years with shared print repositories, and that the two could not be handled in isolation.

Although agreeing that a collective response is needed, several directors worried about having too many options. “I have heard others say we need lots of strategies to keep stuff safe,” said one, “but I’m not sure that’s true.” Another worried about ending up with two or three competing models that would be difficult to sustain. He suggested not investing in any of the options until they get together to build “something we can all get behind.” Keeping track of what is archived by whom raised the specter of major management overhead. One director mused that this might represent a new business for Serials Solutions. All agreed that while it was still early, it would be “nice if the market sorted itself out fast.”

Another concern of the directors was the long-term viability of any e-journal archiving initiative. Several wanted reassurance that their investment would be secure for at least 10 to 20 years. Others argued that it was unrealistic to expect assurances up front, noting that all the options are still experimental and that there is no right solution. Several suggested that it was important for institutions to support different options because it is not clear “which model will win out.” The right answer, one stated, “is that more people must participate in order to uncover the problems and workable solutions.” One director argued that instead of focusing on the existing options, libraries should collectively define what the solution should look like.

Cornell Survey of 12 E-Journal Archiving Initiatives

The directors’ concerns helped shape a questionnaire that our team used to survey e-journal archiving programs. The survey covered six areas: organizational issues, stakeholders and designated communities, content, access and triggers, technology, and resources. The form went through several iterations in response to reviewer feedback and was pilot-tested with one digital archiving entity before being finalized. A version of the final survey form is located in Appendix 1. Project staff sent surveys to 12 e-journal archiving programs in March and held hour-long interviews with key principals (and subsequent follow-up) between April and June 2006.

Several criteria guided the selection of electronic journal archiving initiatives to include in this study. First, each initiative had to have an explicit commitment to digital archiving for scholarly peer-reviewed electronic journals. Second, it had to maintain formal relationships with publishers that include the right to ingest and manage a significant number of journal titles over time. Third, work addressing long-term accessibility had to be under way. Fourth, the efforts had to be by not-for-profit organizations independent of the publishers. Finally, the work had to be of current or potential benefit to academic libraries that have a preservation mandate.

The following 12 e-journal archiving programs met these criteria. Appendix 2 includes longer descriptions of these programs.

Canada Institute for Scientific and Technical Information (CISTI Csi)

The National Research Council of Canada (NRC), Canada’s governmental organization for research and development, was mandated by the National Research Council Act (August 1989) to establish, operate, and maintain a national science library. In that capacity, the NRC hosts CISTI to provide universal, seamless, and permanent access to information for Canadian research and innovation in all areas of science, engineering, and medicine for Canadians, the NRC, and researchers worldwide. To achieve its mission as Canada’s national science library, CISTI has established a three-year program called Canada’s scientific infostructure (Csi) and is partnering with Library and Archives Canada (LAC) to ensure business continuity. This program is creating a national information infrastructure in collaboration with partners to provide long-term access to digital content loaded at CISTI and to support research and educational activities. In 2003, CISTI began loading e-journal content from three publishers and now has loaded close to 5 million articles. Additional content from other publishers in the sciences is planned.

LOCKSS Alliance and CLOCKSS

The Lots of Copies Keep Stuff Safe (LOCKSS) program, based at Stanford University, launched the beta version of its open-source software between 2000 and 2002. LOCKSS intended the software to allow libraries to collect, store, preserve, and provide access to their own, local copies of authorized content. Some 100 participating institutions in more than 20 countries use the LOCKSS software to capture content. About 25 publishers of commercial and open-access content (including large aggregators) participate in the LOCKSS program. In 2005, the LOCKSS Alliance was launched as a membership organization built on the LOCKSS software. The purpose of the alliance is to develop a governance structure and to address sustainability issues. The Controlled LOCKSS (CLOCKSS) initiative, added to the LOCKSS program in 2006, brings together six libraries and twelve publishers to establish a dark archive for e-journals.

Koninklijke Bibliotheek e-Depot (KB e-Depot)

As the national deposit library for the Netherlands, the Koninklijke Bibliotheek (KB) is responsible for preserving and providing long-term access to Dutch electronic publications. To meet that responsibility, the KB started planning for e-journal archiving in 1993 and began to implement an archiving system between 1998 and 2000. It was initially intended as a system in which Dutch publishers would voluntarily deposit their publications for archiving. The KB’s current goal is to include journals from the 20 to 25 largest publishing companies, which produce almost 90% of the world’s electronic STM literature. The KB e-Depot currently offers digital archiving services for eight major publishers.

Kooperativer Aufbau eines Langzeitarchivs Digitaler Informationen (kopal/DDB)

Funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, kopal/DDB is a cooperative project begun in July 2004. A main impetus for kopal has been the need for the national library of Germany, Die Deutsche Bibliothek (DDB), to manage the legal deposit of electronic publications. DDB had been experimenting with electronic journals since 2000; in 2006, Germany enacted legal deposit legislation for electronic publications, making the implementation of a system a priority. Through voluntary agreements with publishers, DDB has acquired a variety of electronic content, including e-journal titles from Springer, Wiley-VCH, and Thieme. Under legal deposit, DDB will start acquiring and adding to kopal all electronic journals published in Germany. In the future, kopal/DDB intends to offer other institutions data archiving services.

Los Alamos National Laboratory Research Library (LANL-RL)

Los Alamos National Laboratory is one of three U.S. national laboratories operated under the National Nuclear Security Administration of the U.S. Department of Energy. LANL-RL has been locally loading licensed backfiles from several commercial and society publishers since 1995. Focusing on titles in the physical sciences, the library maintains content from 10 publishers primarily for the use of the LANL-RL staff, but it also serves a group of external clients who pay for access (LANL charges on a cost-recovery basis). LANL-RL has done substantial research and development work on repository and digital object architecture for long-term maintenance of electronic journal contents. A major focus of the research and development work has been the creation of the aDORe repository.

National Library of Australia PANDORA (NLA PANDORA)

The NLA selects e-journals from its Australian Journals Online database for preservation in PANDORA (Preserving and Accessing Networked Documentary Resources of Australia), which was established in 1996. E-journals is one of six categories of online publications included in PANDORA, which lists 1,983 journals published in Australia. Of these, 150 are commercial titles. The NLA released the first version of the PANDORA Digital Archiving System (PANDAS) in 2001.

OCLC Electronic Collections Online (OCLC ECO)

OCLC launched ECO in June 1997 to support the efforts of libraries and consortia to acquire, circulate, and manage large collections of electronic academic and professional journals. It provides Web access through the OCLC FirstSearch interface to a growing collection of more than 5,000 titles in a wide range of subject areas from more than 40 publishers of academic and professional journals. Libraries, after paying an access fee to OCLC, can select the journals to which they would like to have electronic access. OCLC has negotiated with publishers to secure for subscribers perpetual rights to journal content. In addition, OCLC has reserved the right to migrate journal backfiles to new data formats as they become available.

OhioLINK Electronic Journal Center (OhioLINK EJC)

The Ohio Library and Information Network is a consortium of Ohio’s college and university libraries, comprising 85 institutions of higher education and the State Library of Ohio. OhioLINK’s electronic services include a multipublisher Electronic Journal Center (EJC), launched in 1998, which contains more than 6,900 scholarly journal titles from nearly 40 publishers across a wide range of disciplines. OhioLINK has declared its intention to maintain the EJC content as a permanent archive and has acquired perpetual archival rights in its licenses from all but one publisher.

Ontario Scholars Portal

Launched in 2001, the Ontario Scholars Portal serves the 20 university libraries in the Ontario Council of University Libraries (OCUL). The portal includes more than 6,900 e-journals from 13 publishers and metadata for the content of an additional 3 publishers. The primary purpose of the portal is access, but the consortium has made an explicit commitment to the long-term preservation of the e-journal content it loads locally. The initiative began with grant funding but as of 2006 became self-funded through tiered membership fees.

Portico

Publicly launched in 2006, Portico is a third-party electronic archiving service for e-journals, and serves as a permanent dark archive. E-journal availability (other than for verification purposes) is governed by specific “trigger events” resulting from substantial disruption to access from the publishers themselves. A membership organization, Portico is open to all libraries and scholarly publishers, which support the effort through annual contributions. As of July 1, 2006, 13 publishers and 100 libraries participated in Portico.

PubMed Central

Launched in February 2000, PubMed Central is NIH’s free digital archive of biomedical and life sciences journal literature, run by the National Center for Biotechnology Information of the National Library of Medicine (NLM). PubMed Central encompasses about 250 titles from more than 50 publishers. It prefers that the complete contents for participating titles be submitted, but it will accept at minimum the primary research content, and it allows publishers to delay deposit by a year or more after initial publication. PubMed Central retains perpetual rights to archive all submitted materials and has committed to maintaining the long-term integrity and accuracy of the archive’s contents.

General Characteristics

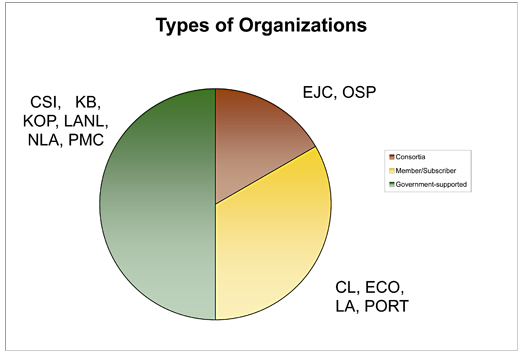

Three organizational types are represented among the twelve programs, as presented in Figure 1. The largest category includes government-supported efforts, with five of the six sponsored by a national library (CISTI Csi, KB e-Depot, kopal/DDB, NLA PANDORA, PubMed Central). LANL-RL receives funding from the U.S. Department of Energy and the U.S. Department of Defense. Two (OhioLINK EJC and the Ontario Scholars Portal) represent consortia that aggregate content primarily for access but have assumed archiving responsibility. Four (CLOCKSS, LOCKSS Alliance, OCLC ECO, and Portico) are member or subscriber initiatives, with all except ECO launched specifically to address digital archiving issues.

|

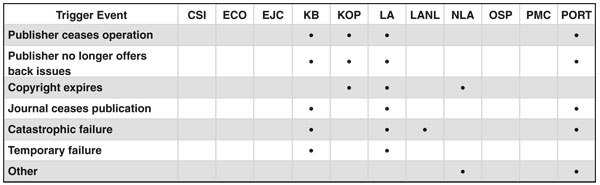

Fig. 1. Types of organizations included in survey

These programs are of recent origin. The oldest (LANL-RL) began in 1995, and four were launched within the past two years. Seven of the programs provide ongoing access to content and five limit access to current subscribers or members. Two (PubMed Central and NLA PANDORA) are open to all, but access to some material may not occur immediately following publication (this waiting period creates a “moving wall” for access). Five provide current access only for auditing purposes and for checking the integrity and security of systems and content; otherwise, access will be given after a trigger event occurs. A trigger event may occur, for example, when a publication ceases to be available online because of publisher failure or lack of support, a major disaster, or technological obsolescence.

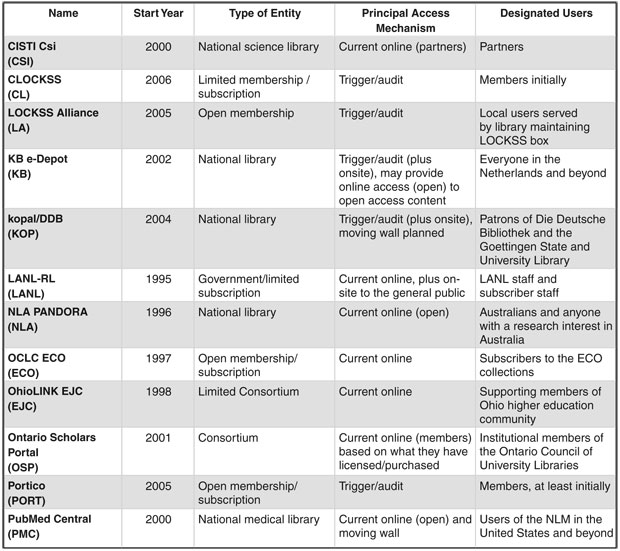

Table 1 compares major attributes for the group, including year of inception, organizational type, access mechanisms, and designated users (i.e., those who receive access whenever it is provided).

|

Table 1. Major attributes of programs surveyed

Note: For the purposes of this report, the abbreviations listed in the left-hand column above will be used for all figures and tables. CLOCKKS was not considered as a separate entity from LOCKSS during the initial round of survey and interview and, therefore, will not be listed separately in many tables.

Assessing E-Journal Archiving Programs

Our team compiled and analyzed the survey responses in May and June 2006, freezing the addition of new information on July 1. A set of indicators for assessing the e-journal archiving programs was derived, in part, from two statements. The first is the Minimum Criteria for an Archival Repository of Digital Scholarly Journals, issued in May 2000 by the DLF. The second is the minimal set of services for an archiving program represented in the “Urgent Action” statement noted above.

As a result of this work, we identified seven indicators of a program’s viability. In meeting its obligations to archive e-journals, the repository should

- have both an explicit mission and the necessary mandate to perform long-term e-journal archiving;

- negotiate all rights and responsibilities necessary to fulfill its obligations over long periods;

- be explicit about which scholarly publications it is archiving and for whom;

- offer a minimal set of well-defined archiving services;

- make preserved information available to libraries under certain conditions;

- be organizationally viable; and

- work as part of a network.

|

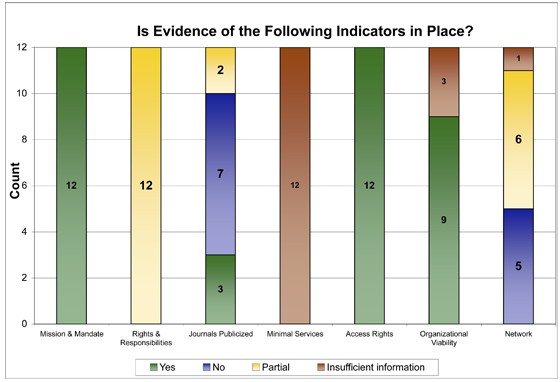

Fig. 2. Measuring e-journal archiving programs against seven indicators

Figure 2 shows our estimate of the current state of program viability for the 12 e-journal archives under review based on the seven indicators. These programs have secured their mandates, defined access conditions, and are making good progress toward obtaining necessary rights and organizational viability, but room for improvement is apparent in three key areas: content coverage, meeting minimal services, and establishing a network of interdependency.

A discussion of the seven indicators follows.

Indicator 1: Mission and Mandate

The repository should have both an explicit mission and the necessary mandate to perform long-term e-journal archiving.

All 12 programs confirmed that their missions explicitly committed them to long-term e-journal archiving, and each has negotiated with publishers to secure the archival rights to manage journal content. Many publishers are willing to participate in these programs in part to protect their digital assets and in response to increasing demand from their principal customers. For example, the five largest STM publishers—Blackwell, Elsevier, Springer, Taylor & Francis, and Wiley—are all engaged in more than one of the e-journal archiving efforts reviewed in this report. Their participation, however, is voluntary, and at least one other publisher refused to grant OhioLINK EJC archival rights as part of its license agreement. E-journal archiving efforts could be strengthened considerably if publishers were required by legislative mandate or as a precondition in license arrangements to deposit their content in suitable e-journal archives.

The Role of Legal Deposit in E-Journal Archiving

More and more nations are requiring the deposit of electronic publications, including electronic journals, in their national libraries. Both the British Library and Library and Archives Canada, for example, are designing electronic-deposit repositories, and Germany recently passed a law that mandates the deposit of German publications, a move that will strengthen kopal/DDB’s program.9 Other nations are expected to follow suit.

While legal deposit is often implemented as a requirement for copyright protection, in practice it can also become an important component of a digital preservation program. Legal deposit laws provide the designated deposit libraries with both an explicit mission and a mandate to preserve a nation’s publications. Once a journal has been deposited, the repository library is responsible for its preservation.

One question is whether legal deposit requirements will obviate the need to establish other e-journal archiving programs. We suggest that it will not, for at least four reasons. First, and most important, while most of the laws are intended to ensure that the journals will be preserved, there is less clarity as to how one can gain access to those journals. In almost all cases, one can visit the national library and consult an electronic publication onsite. It is unlikely, however, that the national libraries will be able to provide online access to remote users in the event of changes in subscription models, changed market environments, or possibly even publisher failure. The recently revised “Statement on the Development and Establishment of Voluntary Deposit Schemes for Electronic Publications,” endorsed by both the Committee of the Federation of European Publishers (FEP) and the Conference of European National Librarians (CENL) and intended to serve as a model for national deposit initiatives, makes no mention of access beyond the confines of the national legal deposit library, leaving such issues to separate contractual arrangements with the publishers (CENL/FEP 2005). None of the national deposit programs we surveyed currently has the capability to serve as a distributor of otherwise unavailable archived journals.

Second, because legal deposit requirements are so new, the ability of the national libraries to preserve content is largely untested. Spurred by the requirements of legal mandates to acquire and preserve digital information, the national libraries have made tremendous strides in developing digital preservation programs. Many advances in our understanding of digital preservation have come through the work of the KB, the NLA, and other pioneering national libraries and archives working in this area. None of these libraries, however, would claim that it has developed the perfect, or only, solution to digital preservation. At this early stage in our knowledge, it is important to have competing digital preservation solutions that can, over time, help us develop a consensus as to what constitutes best practice.

Third, while the movement for national digital deposit legislation seems to be spreading, major gaps remain. In many cases, such as in the Netherlands, the deposit program is a voluntary agreement between the library and the publishers. Publishers are encouraged, but not required, to deposit electronic material. In other cases, most notably the United States, there is neither mandatory legal deposit for electronic publications nor clear evidence that the Copyright Office could demand the deposit of electronic publications (Besek 2003). At a minimum, the United States will need to adopt strong mandatory digital deposit legislation if legal deposit is ever to replace library-initiated preservation.

Finally, and somewhat paradoxically, the concept of national publications is becoming problematic, especially when dealing with electronic journals. Elsevier, for example, may be headquartered in the Netherlands, but does that make all its publications Dutch and subject to any future deposit laws in the Netherlands—even when those journals may have a primarily U.S.-based editorial board and may be delivered from servers based in a third country?

Although legal deposit may not be the silver-bullet solution to archiving e-journals, it is clearly an important component of the preservation matrix. If nothing else, a legal requirement that would force publishers to deposit e-journals in several national deposit systems (because of the international nature of publishing) would create pressure for standard submission formats and manifests for e-journal content. In addition, once material is preserved, it may be possible to revisit the trigger events that allow access to the content and even to permit remote access in narrow circumstances. The national libraries are also well positioned to develop technical expertise related to digital preservation and to share that expertise. For these reasons, we hope that efforts to develop more e-journal deposit laws will continue. It would be particularly beneficial if the U.S. Copyright Office started requiring deposit of electronic journals for copyright protection and the Library of Congress (LC) assumed responsibility for the preservation of those journals.

The Role of Open-Access Research Repositories in E-Journal Archiving

A development closely related to mandatory legal copyright deposit is the mandatory deposit of funded research into an open-access research repository, such as PubMed Central or arXiv. To date, participation in such repositories has been voluntary, and the results have been mixed. NIH, for example, estimates that only 4% of eligible research is making its way into the PubMed Central online digital archive as a result of the voluntary provisions of NIH’s Policy on Enhancing Public Access to Archival Publications Resulting from NIH-Funded Research, implemented in May 2005 (DHHS 2006). Indeed, member publishers of the DC Principles Coalition fiercely contested the idea of a “mandated central government-run repository” (AAP, AMPA, DCPC 2004).

Several initiatives now under way could alter the voluntary nature of most agreements. In the United Kingdom, the Wellcome Trust and the Medical Research Council have ordered that the final copies of all research they fund be deposited in the UK PubMed Central, and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council has mandated that publications from research it funds after October 1, 2006, will be deposited “in an appropriate e-print repository” (BBSRC 2006). Research Councils UK (RCUK) has encouraged the other U.K. research councils to consider deposit of funded research in an open-access repository.10 In the United States, a recent NIH appropriations bill was modified in committee to mandate the deposit of copies of all NIH-funded research in an open-access repository within 12 months of publication (Russo 2006). In addition, Senators John Cornyn (R–TX) and Joe Lieberman (D–CT) have introduced the Federal Research Public Access Act of 2006 (FRPAA), which would require that research funded by the largest federal research agencies and published in peer-reviewed journals be deposited and made openly accessible in digital repositories within six months of publication. Publishers oppose this proposed legislation.11

Given that more and more funded research is going to find its way into open-access repositories, an obvious question is whether libraries can rely on those repositories to preserve that information. There are at least two reasons why we would not recommend relying solely on open-access repositories for an archiving solution at this time.

First, while much research that appears in journals is funded by major U.S. or U.K. funding sources, many articles are not so funded. Consequently, much information will remain outside open-access repositories for the foreseeable future. Open-access article repositories are unlikely to function as substitutes for electronic journals.

Second, open-access repositories are not necessarily digital preservation solutions, although sometimes their names suggest otherwise. For example, one of the oldest open-access repositories, arXiv, suggests by its name that it is involved with preservation, yet there is nothing in the repository software that will ensure the preservation of deposited digital objects. Similarly, the protocol that links many preprint servers was named the Open Archives Initiative Protocol for Metadata Harvesting (OAI-PMH), suggesting that its activities are related to the Open Archival Information System (OAIS) framework. In reality, OAI and OAIS have nothing to do with each other (Hirtle 2001). Open “archives” are primarily concerned with providing open access to current information and not with long-term preservation of the contents.

In its draft position statement on access to research outputs, issued June 28, 2005, RCUK noted the distinction:

RCUK recognises the distinction between (a) making published material quickly and easily available, free of charge to users at the point of use (which is the main purpose of open access repositories), and (b) long-term preservation and curation, which need not necessarily be in such repositories. . . . [I]t should not be presumed that every e-print repository through which published material is made available in the short or medium term should also take upon itself the responsibility for long-term preservation.

RCUK’s proposed solution was not to assume that the open-access repositories would perform preservation, but instead to work with the British Library and its partners to ensure the preservation of research publications and related data in digital formats.

Similarly, the Cornyn/Lieberman bill does not assume that institutional or subject-based repositories will be able to preserve research articles. Instead, it requires that their long-term preservation be done either in a “stable digital repository maintained by a Federal agency” or in a third-party repository that meets agency requirements for “free public access, interoperability, and long-term preservation.”

In sum, the existing open-access research repositories (other than PubMed Central) are unlikely to qualify at this time as stable digital repositories. Libraries should therefore not presume that the scholarly record has been preserved just because it has been deposited in such a repository. At the same time, initiatives such as those from the RCUK and in FRPAA could be important to the development of digital preservation because they would force agencies either to develop digital preservation solutions themselves or define the requirements for third-party solutions.

Recommendations

- More effort needs to go into extending the legal mandate for preserving e-journals through legal deposit of electronic publications around the world, to formalize preservation responsibility at the national level.

- As part of their license negotiations, libraries and consortia should strongly urge publishers to enter into e-journal archiving relationships with bona fide programs.

- Publishers should be overt about their digital archiving efforts and their relationships with various digital archiving programs. The five largest STM publishers are all engaged in more than one of the e-journal archiving efforts reviewed in this report, but only one (Elsevier) presents its digital archiving program on its Web site. Several others have announced their archiving policies in newsletters or press releases—which may still be included on their Web sites as part of a publicity archive—but it can be difficult to locate this information.12

- Programs with responsibility to provide current access and archiving should publicize their digital archiving responsibilities both to publishers and to the research library community. Our discussions with library directors revealed that several of them were unaware of PubMed Central’s archiving responsibility or that it could serve as part of their preservation safety net.

- As the “Urgent Action” statement stipulates, research libraries should not sign licenses for access to electronic journals unless there are provisions for the effective archiving of those journals. The archiving program should offer at least the minimal level of services defined in the “Urgent Action” statement. In addition, the programs should be open to audit, and, when certification of trusted digital repositories is available, they should be certified. Unless e-journal content is preserved in such a repository, research libraries should not license access.

Indicator 2: Rights and Responsibilities

Rights and responsibilities associated with preserving e-journals should be clearly enumerated and remain viable over long periods.

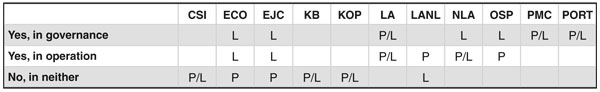

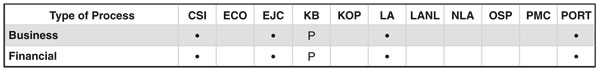

Closely related to mission and mandate is the need for clarity of a repository’s rights and responsibilities vis-à-vis publishers, distributors, and content creators. Although a publisher may grant archiving rights to a repository, the circumstances surrounding the exercise of these rights may not be uniform or clearly enumerated—or even fully understood when the contract is written. Including input from research libraries and publishers in the governance or operation of the repository would be a useful way to monitor policies as circumstances change (Table 2).

Table 2. Responses to question: “Do publishers have any voice in the governance/operation of your e-journal archiving program?” (P = publishers; L = libraries)

The following three questions should be carefully considered in laying the foundation for digital archiving responsibility:

First, do the contracts consider all intellectual property rights held by publishers, creators, and technology companies that pertain to the content, and do they convey to the repository the right to perform necessary archiving functions to prolong the life of the content? Such rights can include basic permission to copy or reformat material, or both. They extend to bypassing copy and access restrictions, expiration, and other embedded technological controls. If not granted explicit permission, the repository may be unable to provide ongoing access through copying, migration, or reproduction.

Second, does the publisher or its successor reserve the right to remove or alter content from the archival institution under certain circumstances? If so, the archived content could be placed at risk. When asked whether agreements with publishers allow the repository to continue to archive content if the publisher is sold or merges with another company, seven programs answered “yes,” one answered “no,” and two were unsure. PubMed Central reported an instance when a publisher acquired one of the journals previously included and decided not to participate further, so new content has not been added. The content already in the repository remained. OhioLINK EJC’s publisher agreements make no mention of exceptions caused by future changes in ownership. Could their rights under these conditions be only indirectly protected? The KB e-Depot and kopal/DDB recommend that publishers continue to ensure compliance with archiving agreements in the event of mergers, buyouts, or discontinuation of publishing operations, but these recommendations are not legally binding. Elsevier reserves the right to remove content from the KB e-Depot if there is a breach of contract; the LANL-RL indicated that material received could be kept indefinitely, “as long as previously agreed-upon usage restrictions are adhered to.” CISTI Csi will seek to obtain a new agreement in the case of a merger or title transfer to a new publisher.13

Finally, are agreements with publishers regarding archival rights of limited duration? If so, the circumstances governing preservation responsibilities may be subject to change. Four of the twelve repositories reported that their contracts are of fixed, limited duration. They are reviewed regularly, at which time they may be renewed but also canceled. The remaining contracts are of indefinite duration or automatically renewable; all have cancellation options.

Recommendations

- Once ingested into the digital archive repository, e-journal content should become the repository’s property and not subject to removal or modification by a publisher or its successor.

- In case of alleged breach of contract, there should be a process for dispute mediation to protect the longevity and integrity of the e-journal content.

- Contracts need to be reviewed periodically, because changes in publishers, acquisitions, mergers, content creation and dissemination, and technology can affect archiving rights and responsibilities. Continuity of preservation responsibility is essential.

- A study should be conducted to identify all necessary rights and responsibilities to ensure adequate protection for digital archiving actions, so that these rights are accurately reflected in contracts and widely publicized.

- Research libraries and consortia should pressure publishers to convey all necessary rights and responsibilities for digital archiving to e-journal archiving programs (i.e., the same rights should be conveyed in all archiving arrangements).

Indicator 3: Content Coverage

The repository should be explicit about which scholarly publications it is archiving and for whom.

Although this indicator seems to be straightforward, it is surprisingly difficult to identify what publications are being preserved and by whom. Six of the programs make public their list of publishers (OhioLINK EJC, PubMed Central, CLOCKSS, OCLC ECO, LOCKSS Alliance, Portico), three do so indirectly (KB e-Depot, CISTI Csi, Ontario Scholars Portal), and three do not (LANL-RL, NLA PANDORA, kopal/DDB). Even when the publishers are known, one should not assume that all journals owned by that publisher are included in the archiving programs. For instance, PubMed Central reported the largest number of publishers represented in its holdings, but the smallest number of titles of the 12 programs surveyed.

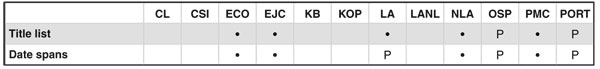

Locating a list of specific titles included is even more difficult. When asked whether they made an up-to-date, definitive list of titles available to the public, five responded “yes” (NLA PANDORA intersperses the list of journal titles with other content, with no ability to sort on e-journals only; the LOCKSS Alliance is building its list alphabetically by journal title). Five said “no,” (the KB e-Depot and kopal/DDB indicated that they will archive all publications published in their respective countries). The remaining two programs plan to make such a list available. Further, even when the publications are listed, it is difficult to determine what date spans are included (only four repositories list this information) and how complete the contents of the publication are. For instance, the LANL-RL purchased backfiles of the Royal Chemistry Society journals from their inception to 2004, but is not receiving current content for local loading and archiving and does not intend to purchase it. Table 3 shows the availability of title lists and date spans by e-journal archiving repository. Maintaining content currency is a moving target; all repositories indicated they expect to add new titles and, indeed, during the course of our investigation new titles and publishers were being added frequently.

Table 3. Responses to question “Do you make information about journal titles and date spans included in your program available to the public?” ( • = yes; P = plan to within six months)

The pace of consolidation within scholarly publishing also creates dilemmas for those attempting to chronicle the state of the industry at any one time. Ownership of publishing houses, imprints, and individual titles is in constant flux, making it difficult to accurately associate large lists of titles with the correct publisher. In recent years, large companies with no name recognition as publishers have swallowed up a number of venerable publishing houses. Should these titles continue to be listed under the familiar, original publisher or by the new owner? Particularly complex are cases wherein a publisher has sold a portion of its titles or entire imprints but held on to others.

When evaluating data from e-journal archiving initiatives, it is sometimes impossible to tell whether lists of participating publishers or the names of publishers associated with particular titles reflect current status or are based on legacy metadata. For example, some initiatives still list Academic Press as a separate entity, while others have incorporated its titles under the current owner, Elsevier. When an initiative lists titles from Kluwer, is it referring to Kluwer Academic Publishers, which was purchased by Springer from Wolters Kluwer in 2004, or to Kluwer Health, which is still part of the original firm and includes labels such as Adis International and Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins? If complete title listings are available, it may be possible (though onerous) to make such a distinction, but lists are not always available.

Thus, the publisher listings presented here should be viewed as nothing more than a fuzzy snapshot of circumstances on July 1, 2006. The kind of precision that would allow us to determine the archived status of specific titles and publishers is not possible given the market’s volatility and ambiguity in the current data.

Adding to the confusion about which titles and publishers are included in archiving initiatives is the fact that not all the “publishers” listed are truly publishers. Some are really aggregators—essentially republishers that provide electronic publication, marketing, and dissemination services for (usually) small scholarly societies that produce only one or a few titles and therefore benefit from aggregation to achieve visibility, critical mass, and state-of-the-art electronic publishing services.

Two prominent aggregators that turned up many times in our surveys are BioOne and Project MUSE. BioOne is a nonprofit aggregator that disseminates noncommercial titles in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. Most of the original publishers contracting with BioOne are scholarly societies and associations. As of July 1, 2006, BioOne handled 84 titles from 66 publishers. Even though none of the e-journal archiving initiatives we surveyed listed the American Association of Stratigraphic Palynologists as a publisher, its lone journal, Palynology, is included in LOCKSS Alliance, OhioLINK EJC, and Portico, by virtue of its contract with BioOne.

Project MUSE fills a similar niche for small publishers in the humanities, arts, and social sciences. Incorporating more than 300 journals from 62 publishers, predominantly university presses, as of July 1, 2006, Project MUSE provides a portal and search facility that brings together many related titles. But MUSE also boasts that it provides a “stable archive.” The overview on its Web site states the following:

It is a MUSE policy that once content goes online, it stays online. As the back issues of journals increase annually, they remain electronically archived and accessible. We also have a permanent archiving and preservation strategy, including participation in LOCKSS, maintenance of several off-site mirror servers, and deposition of MUSE content into third-party archives.

MUSE participates in LOCKSS Alliance, OhioLINK EJC, and OCLC ECO. So, despite the absence of the George Washington University Institute for Ethnographic Research on the publisher listings of any of the e-journal archiving initiatives included here, its journal, Anthropological Quarterly, is being archived.

Other aggregators that are participating in at least one of the archives include HighWire Press (which hosts nearly 1,000 titles from large and small publishers and is affiliated with LOCKSS Alliance), the LOCKSS Humanities Project, the History Cooperative, and ScholarOne, Inc.

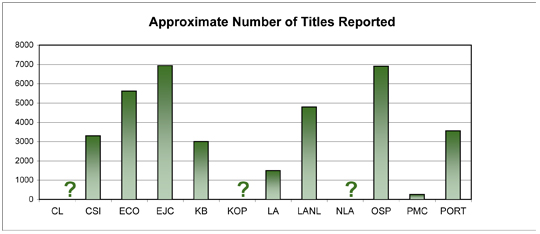

With all these caveats in mind, the number of titles included in these 12 programs is impressive, exceeding 34,000, as shown in Figure 3.

Fig. 3. Approximate number of titles included in e-journal archiving programs

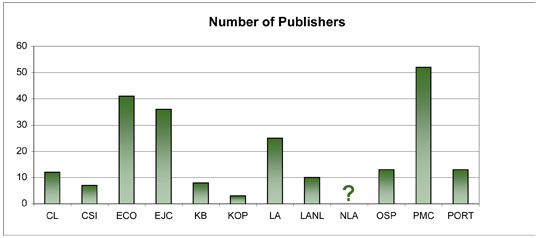

Because there is no definitive list of titles covered in all these programs, the degree of overlap in content coverage is unknown. We were able to identify 220 publishers mentioned as participating in one or more of the e-journal archiving programs under review. We omitted PANDORA because the NLA preserves only Australian publications and does not maintain e-journal publisher data separately. Figure 4 provides the total publisher count for each e-journal archiving program. Appendix 3 lists the publishers in each archiving program.

Fig. 4. Number of publishers included in the 12 e-journal archiving programs surveyed

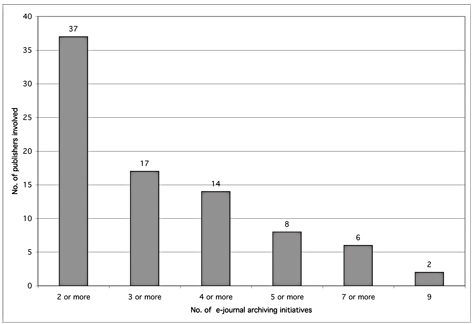

The number of unique publishers in this pool is 128 (58% of the total). Of those, 91 (71%) are participating in only 1 program; 20 (16%) are involved in 2 programs. The major publishers are well represented in multiple arrangements. As Figure 5 reveals, 17 of them (13%) are involved in 3 or more programs and 6 of them (5%) are involved in 7 or more programs. Appendix 4 identifies the publishers included in more than one e-journal archiving arrangement.

Although there may not be complete overlap in content in each program, it appears that there is much redundancy for the major publishers of STM e-journals, especially those in English, many of which have their own archiving programs. Other disciplines, smaller publishers (especially independent Web publications of a dynamic nature), and most material published in non-Roman alphabets are less represented in general and particularly in multiple arrangements. They are also less likely to have developed a full-fledged archiving program in-house.

Fig. 5. Publisher overlap

It is unclear what the trend toward amalgamation of smaller presses into larger entities will mean for digital archiving, but it might prove beneficial. Recognizing the extent of at-risk e-journals in the humanities, LOCKSS launched its Humanities Project in 2004. Selectors at a dozen research libraries are participating in the project to identify significant content in the humanities for preservation, and programmers at those institutions are developing the plug-ins needed to capture the content, once the relevant publishers sign on.14

In addition to being transparent about the list of journals included and the date spans covered for each journal, archiving programs should be explicit about the content captured at the journal level (see next section). Content captured can vary by publisher as well as by journal. Given the differing archiving approaches used, it is likely that the extent of content captured for a particular journal held by more than one archive will vary among archives.

Recommendations

- E-journal archive repositories need to be more overt about the publishers, titles, date spans, and content included in their programs. This information should be easily accessible from their respective Web sites.

- A registry of archived scholarly publications should be developed that indicates which programs preserve them, following such models as the Registry of Open Access Repositories (ROAR), which lists 667 open-access e-print archives around the world, and ROARMAP, which tracks the growth of institutional self-archiving policies.

- Research libraries should lobby smaller online publishers to participate in archiving programs and encourage e-journal programs to include the underrepresented presses; ideally, e-journal programs would cooperate to ensure that they share the responsibility to include these journals. (Only the LOCKSS Alliance allows a library to choose which publications to include.)

Indicator 4: Minimal Services

E-Journal archiving programs should be assessed on the basis of their ability to offer a minimal set of well-defined services.

This indicator is among the most elusive to assess because there is no universally agreed-on set of requirements for digital preservation, no mechanism to qualify (or disqualify) archiving services, and no organized community pressure to require it, although promising work is under way.

In 2003, RLG and NARA established the RLG-NARA Digital Repository Certification Task Force to develop the criteria and means for verifying that digital repositories are able to meet evolving digital preservation requirements effectively. The task force built on the earlier work of the OAIS working groups, especially the Archival Workshop on Ingest, Identification, and Certification Standards. In September 2005, RLG issued the task force’s draft Audit Checklist for Certifying Digital Repositories for public comment. The checklist provides a four-part self-assessment tool for evaluating the digital preservation readiness of digital repositories. A revised version of the checklist is planned for release by the end of 2006.

To further the digital preservation community’s certification efforts, The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation awarded a grant to fund the Certification of Digital Archives project at CRL. This project used the draft RLG audit checklist as a starting point for conducting test audits for four archival programs: Portico, LOCKSS Alliance, the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research, and the KB e-Depot. The results of these test audits are informing the revision of the checklist. The project’s final report, also scheduled for release by the end of 2006, will include recommendations for future developments in the audit and certification of digital repositories.

The Digital Curation Centre in the United Kingdom is conducting test audits of three digital repositories. It has a particular interest in and focus on the nature and characteristics of evidence to be provided by an organization during an audit to demonstrate compliance with the specified metrics. An interesting aspect of its approach is the value and use of evidence provided by observation and testimonials (Ross and McHugh 2005, 2006).

Germany is developing a two-track program for certification. DINI (Deutsche Initiative für Netzwerkinformation), a German coalition of libraries, computing centers, media centers, and scientists, encourages institutions to adopt good repository management practices without being overly prescriptive—steps that would lead to soft certification. The aim of soft certification is to motivate institutions to improve interoperability and gain a basic level of recognition and visibility for their repositories. The nestor project (Network of Expertise In Long-term STOrage of Digital Resources) is investigating the standards and methodologies for the evaluation and certification of trusted digital repositories and embodies rigorous adherence to requirements, leading to hard certification. The principles embraced by the nestor team include appropriate documentation, operational transparency, and adequate strategies to achieve the stated mission. DINI focuses on document and publication repositories at universities for scientific and scholarly communication and had issued 19 certifications as of July 2006. Nestor’s scope goes beyond the realm of higher education and also targets repositories in national and state libraries and archives, museums, and data centers. Nestor is finalizing its certification criteria and has not yet issued any certificates (Dobratz and Schoger 2005; Dobratz, Schoger, and Strathmann 2006).15

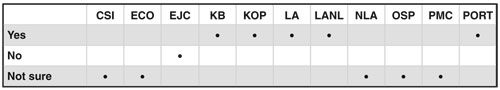

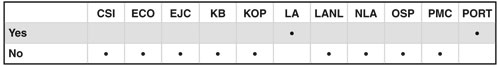

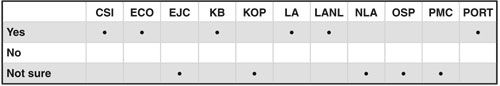

It is not now possible for digital archiving programs to be certified, but when asked whether they would seek to become certified once such a process is in place, five of the e-journal archiving programs indicated they would, one indicated it would not, and five were uncertain or unaware of the certification effort. Table 4 reports their responses.

Table 4. Responses to question: “Will you seek to become a certified repository?” ( • = yes)

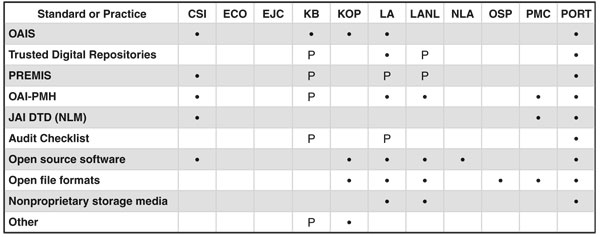

In the absence of a certification process, adherence to digital preservation standards is a potential gauge to the technical viability of a program. Some existing digital preservation standards and best practices provide pieces of the puzzle.16 We asked the surveyed repositories whether they were adhering to or planning to follow some of the key standards in the next six months. Table 5 lists these standards and best practices and provides the repositories’ responses. Of interest is that only 5 of 11 programs report adherence to OAIS, an International Standards Organization standard that is gaining strong purchase in the digital preservation community. NLA PANDORA sees compliance to standards as a long-term goal and aligns with them as much as possible.

Table 5. Responses to question: “Do you follow any of the following standards and best community practices for archiving?” ( • = yes; P = plan to within six months)

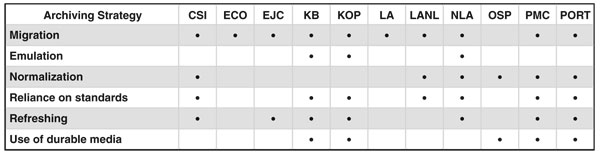

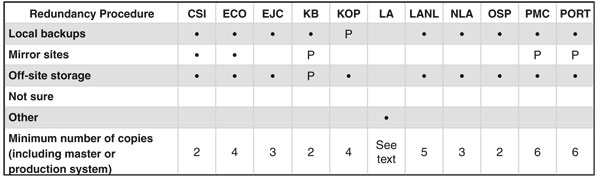

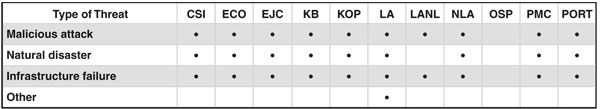

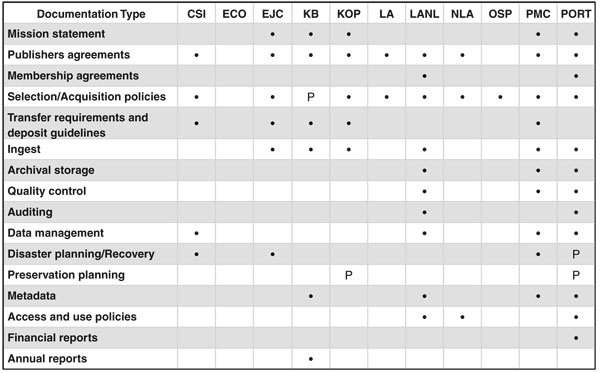

Despite the lack of a means to certify the operation of digital repositories, enough conceptual work has been done to identify minimal expectations of best practices for a less rigorous standard—that of a well-managed collection. Measures such as an effective ingest process with minimal (even manual) quality control, acquiring or generating minimal metadata for digital objects in collections, maintaining secure storage with some level of redundancy, establishing protocols for monitoring and responding to changes in file format and media standards, and creating basic policies and procedural documentation—all acknowledge and address fundamental threats to digital document longevity.

There is widespread agreement about the nature of those threats—information technology (IT) infrastructure failure (hardware, media, software, and networking), built environment failures (plumbing, electricity, and heating, ventilation, and air conditioning), natural disaster, technological obsolescence, human-induced data loss (whether accidental or intentional, internal or external in origin), and various forms of organizational collapse (financial, legal, managerial, societal). There is far less uniformity of thought about the best means to confront each threat, or even which approaches should be considered effective to provide minimal protection.

Not surprisingly, therefore, the programs we surveyed, despite claiming a similar mandate, have chosen a variety of ways to carry it out. The diversity of approaches is healthy and useful, since only time and experience will tell us which techniques are effective. It is critical, however, that existing programs honestly and accurately document their successes and failures. The need for a risk-free mechanism to report negative results was noted in a previous CLIR report, which recommended “establishing a ‘problems anonymous’ database that allows institutions to share experiences and concerns without fear of reprisal or embarrassment” (Kenney and Stam 2002). The recommendation to establish such a system arose again in a more recent paper, which suggested the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s Aviation Safety Reporting System as a possible model (Rosenthal et al. 2005b). We heartily endorse these recommendations and believe that the community should place high priority on creating such a reporting system soon. The only way we will learn about the efficacy (or lack thereof) of various approaches is by having truthful reporting of experiences.

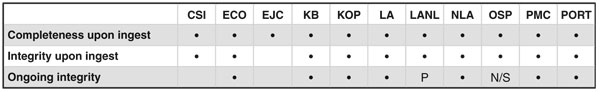

Short List of Minimal Services

As a starting point for documenting the digital preservation services being executed by the programs under review, we chose to assess them by five technical requirements laid out in the “Urgent Call to Action” statement, plus an additional requirement that we believe qualifies for the “short list” of minimal services:

- receive files that constitute a journal publication in a standard form, either from a participating library or directly from the publisher;

- store the files in nonproprietary formats that could be easily transferred and used should the participating library decide to change its archives of record;

- use a standard means of verifying the integrity of ingoing and outgoing files, and provide continuing integrity checks for files stored internally;

- limit the processing of received files to contain costs, but provide enough processing so that the archives could locate and adequately render files for participating libraries in the event of loss;

- guard against loss from physical threats through redundant storage and other well-documented security measures; and

- offer an open, transparent means of auditing these practices.

Our discussion of these services presumes that programs should address not only what the services consist of but also how they intend to implement them.

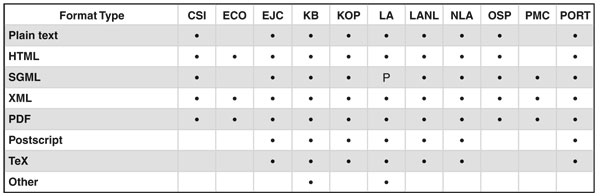

Receive files that constitute a journal publication in a standard form, either from a participating library or directly from the publisher. This ingest-focused requirement encompasses at least two major elements. The first deals with the standard form that received files take. Before delving into specific standards, it is necessary to distinguish two basic approaches that e-journal archiving programs can use to receive the files that constitute a journal publication from the publisher. The most common approach is often referred to as “source-file archiving.” In it, the archival agency receives from the publisher the files that constitute the electronic journal. These could be the standard generalized markup (SGML) files used to produce the printed volumes or the word processing or extensible markup language (XML) files used by the publisher to produce both printed and online products, such as portable document format (PDF) files. Graphic files and supporting material can also be included. In some cases, the files sent to an archival agency can be more complete than what is actually published. For example, a high-resolution image could be preserved even though a lower-resolution image is used on an online access site. PubMed Central and Portico are focused on preserving the source files received from the publishers.

A second approach is to receive the files that constitute the journal as published electronically. We call this approach “rendition archiving,” since it focuses on preserving the journal in the form made available to the public. PDF files are the most common format for displaying journals as published, although some programs also receive the HTML and image files that are used to display a journal to readers. All the programs we surveyed welcome the submission of rendition files, and some, such as OCLC ECO, NLA PANDORA, and the LOCKSS Alliance, are based entirely on preserving and delivering the content as published. The LOCKSS Alliance and NLA PANDORA are special cases of rendition archiving. Rather than relying on rendition files provided by the publisher, they harvest (with the permission of the publishers) files from the publishers’ Web sites.

Each of these approaches has advantages and disadvantages. With source archiving, the most complete version of the e-journal content is preserved. Furthermore, as is discussed in detail below, source-file content is often either delivered in or converted to a few normalized formats, on the assumption that it will be easier to ensure the long-term accessibility of standardized and normalized files. One disadvantage to source archiving is that it requires a large up-front investment, with no assurance that the archive will ever actually be needed. In addition, the presentation of the e-journal content will almost certainly differ from that of the publisher; the “look and feel” of the journal will be lost.

Rendition archiving can maintain the look and feel of the journal, but it may be harder to preserve the content. No one knows, for example, what an effective migration strategy for PDF documents might be. In addition, it may be difficult to preserve the functionality of a dynamic e-journal if harvesting screen “scrapes” of static hypertext markup language (HTML) pages is the preferred ingest solution. On the plus side, the initial costs associated with preserving rendition files are likely to be lower (and, in the case of the harvesting projects, much lower). Migration, normalization, and other preservation activities need take place only when actually needed.

At this point, it is impossible to say which of these two approaches is the better solution to archiving. Those programs that solicit both source files and rendition copies of e-journal content (PubMed Central, Portico, KB e-Depot, kopal/DDB) probably are the safest archiving solution—but at a potentially greater cost.

Since text structure is the aspect of journal publishing that has been subject to the greatest standardization effort, source files are the type most commonly produced in a standard form. Several SGML and XML DTDs (document type definitions) have been devised specifically to support publishing of scholarly journal articles. One of the most popular is the NLM/NCBI (National Library of Medicine/National Center for Biotechnology Information) Journal Archiving and Interchange DTD. The full Journal Archiving and Interchange DTD Suite also includes modules that describe the graphical content of journal articles and certain nonarticle text, including letters, editorials, and book and product reviews. Acceptance of the Journal Archiving and Interchange DTD received a major boost in April 2006 when LC and the British Library announced support for the migration of electronic journal content to the NLM DTD standard, “where practicable” (Library of Congress 2006).17 Four of the programs we surveyed currently use the NLM DTD.

Use of XML and SGML with DTDs designed for journal articles and other components has implications for “standard form” of structure and interchange capability at the lowest levels. The definition of a character in the XML specification is based on the Unicode set. We queried the programs about the Unicode compatibility of their systems and found that at least some components of legacy systems (ScienceServer sites in particular) lacked it. With many publishers now supplying both journal content and metadata in XML, this has caused problems, particularly with the display of bibliographic data for some access-driven programs. We heard complaints that publishers had made the switch to Unicode compliance without giving the archive enough time to adjust its ingest procedures, resulting in incompatibilities. Two archives (PubMed Central and Portico) mentioned that despite being fully Unicode compliant, they could not support non-English metadata because of limitations in their ability to perform quality control and, in PubMed Central’s case, because the search-and-retrieval system is based on English-language indexing and text matching.

Given that many of the programs profiled here are research driven, it is not surprising that they are trying to break new ground in repository development. Consequently, some of the “standard forms” used in the programs are unique to them. In LANL-RL’s new aDORe repository, digital objects are represented using MPEG-21 DID (digital item declaration) and stored in an XML tape, while kopal/DDB has developed a Universal Object Format (Steinke 2006) for archiving and exchange of digital objects. Unfortunately, nothing yet qualifies as “universal” when it comes to digital objects. (As a cynic once said, “The nice thing about standards is that there are so many to choose from.”) Until digital repository design matures and stabilizes, exchange of complex digital objects (i.e., archival information packages, or AIPs) among repositories will be less than transparent. However, proposals are emerging for facilitating the exchange of complex digital objects between repositories and archives.18 Experimentation with a variety of approaches is appropriate at this stage of archive development. We also recommend that e-journal archives using different standards begin examining interoperability issues for digital objects and metadata, with an eye on maximizing compatibility.

There is as yet no standard form for source files. Although many programs prefer, and some require, files to be delivered as PDFs, no specific version of PDF is required. No program requires that PDFs adhere to ISO 19005-1 (PDF/A-1), and we are not aware of any major publishers that offer their files in that format.

Asked about the existence of file-format requirements (or preferences) for ingest, eight programs said they have such requirements, and half of them provided us with technical documentation describing them. Four do not (LOCKSS Alliance, Ontario Scholars Portal, NLA PANDORA, Portico). LOCKSS Alliance and NLA PANDORA harvest files from the Web and take whatever content can be delivered through Web protocols.

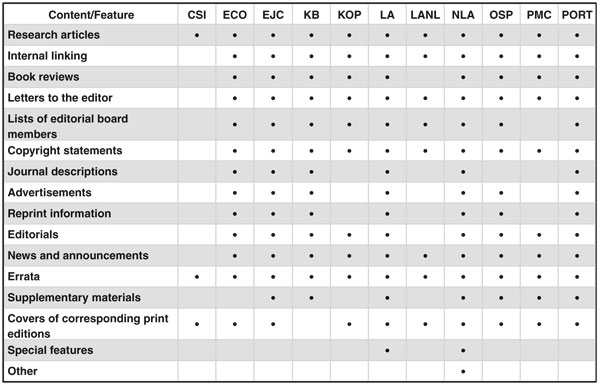

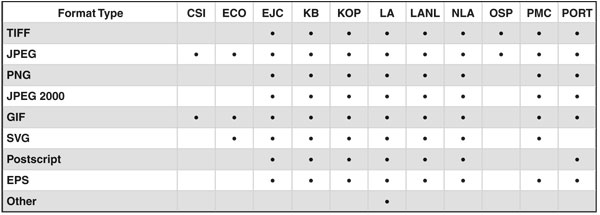

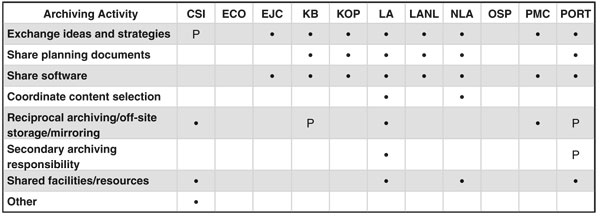

The second major element of this minimal service is the receipt of “files that constitute a journal publication.” Identifying the entirety of a journal publication in print is a straightforward matter, but the components of e-journals are more varied both in form and content and are far less tightly bound together. The lack of an established standard for what constitutes the essential parts of an e-journal was made abundantly clear by the nonuniform responses to our questions about which journal content types and features each archiving program includes (see Table 6).

Table 6. Journal content types and features

All said they include research articles and errata, but beyond that there was no consistency. Athough most said they maintain “whatever the publisher sends,” many do not include advertisements (which are often generated on-the-fly in a user-dependent manner) and certain other non-editorial content. Some do not capture supplemental materials, and even fewer are able to capture external features associated with publisher Web sites, such as discussion forums and other interactive content. Although it encourages the deposit of all journal components, PubMed Central, for example, requires only that research articles be provided; the presence of other kinds of content may vary among publishers, and even among titles.

The programs are aware that different publishers send different kinds and numbers of files for each title, but they seem less aware of what those components are. Survey comments made it clear that some responses to this question were guesses. Particularly for the access-driven programs, the focus is primarily research articles. Several respondents said that although they keep everything they receive, they are not necessarily able to provide access to all components.

There is likewise considerable variability within programs, because publishers have different definitions of what constitutes a complete e-journal. With no means to standardize journal components, and given that publishers are generally unable to provide manifests of how many files of what type the archive is supposed to be receiving, uncertainty at the receiving end is inevitable. Several programs noted that the lack of publisher manifests was a big problem. There is less ambiguity with programs that harvest content from publisher Web sites (NLA PANDORA and LOCKSS Alliance). Since the content is coming directly from the publisher’s officially disseminated version, the only potential for missing components is if the harvesting itself is incomplete.

Users read and access the content of e-journals very differently than they do print journals (Olsen 1994). As more scholarly publishers eliminate print versions of their titles, it is possible that certain once-common features, such as advertisements or conference announcements, will be dropped or disseminated by different means (e.g., blogs or RSS feeds). The scholarly publishing landscape is not stable enough to prescribe what components (at minimum) constitute a journal publication in electronic form. But publishers need to do a better job of specifying exactly what they call a complete issue, and archiving programs need to pay more attention to exactly what they are receiving.

Store the files in nonproprietary formats that could be easily transferred and used should the participating library decide to change its archives of record. Use of nonproprietary formats has long been recognized as a strategy to fight obsolescence and improve the portability of digital objects. Depending on the ingest and archive approach of a particular program, the role of nonproprietary formats may be to

- take everything and store it in the supplied format (e.g., OhioLINK EJC, Ontario Scholars Portal, LOCKSS Alliance);

- take everything (or nearly so), preserve the original, but normalize it on ingest (e.g., Portico); or

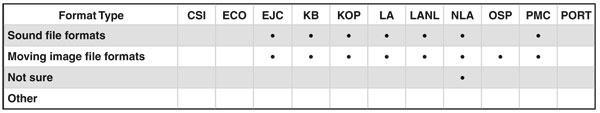

- require use of a particular format or formats for deposit (e.g., PubMed Central, KB e-Depot, OCLC ECO).