Number 131 September/October 2019

ISSN 1944-7639 (online version)

Contents

Three Questions with Don Waters

Are We Doing Enough to Manage and Preserve Born-Digital Content?

Follow the DLF Forum and Related Events

Call for Host Institutions: Postdoctoral Fellowship Program

CLIR Issues is produced in electronic format only. To receive the newsletter, please sign up at https://www.clir.org/pubs/issues/signup. Content is not copyrighted and can be freely distributed.

Follow us on Twitter @CLIRNews, @CLIRHC, @CLIRRaR @CLIRDLF

Like us on Facebook @CLIRNews

Three Questions with Don Waters

Editor’s note: In this installment of our occasional series, “Three Questions,” we hear from Donald J. Waters, who recently retired from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, where he served as program officer for scholarly communications for two decades.

You were the first director of the Digital Library Federation. What attracted you to the job? What was your hope then for the evolution of digital libraries, and what is it now?

Few careers move in a straight line, and I am acutely aware that serendipity influenced my own choices as much as prior experience and interest. Now that I have left my position at The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, I appreciate the chance you offer in this question to reflect on my career at the Foundation, in part, by putting it in the context of what came before at the Digital Library Federation (DLF). However, the answer to what attracted me to the position of DLF director depends, in turn, on an accumulation of experiences I had at Yale University during the 15 years before I joined the DLF.

For example, at the School of Management in the mid-80s, I was director of computing and responsible for setting up the school’s first personal computer laboratory. At the university library beginning in 1987, I oversaw the installation of Yale’s first integrated library system, which came online just before the formation of the World Wide Web. I was also the principal investigator for Project Open Book, an effort supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities to explore how to digitize books and serials originally microfilmed as part of the effort to preserve brittle books in the nation’s research libraries. In addition, during the mid-1990s, while I was an associate university librarian at Yale, I served as the co-chair of the Task Force on Archiving Digital Information, which the Commission on Preservation and Access and the Research Libraries Group had jointly created. All these experiences impressed upon me how important digital tools and information were becoming to research and learning in higher education.

Of course, my experiences at Yale with the rapid growth of personal computers, the internet, and digital information mirrored those of many in other universities and libraries. What attracted me to serve as director of the DLF was the consensus among its founding members that this emerging digital environment would be central to the creation and dissemination of new knowledge going forward. Further, they agreed that research and learning would not advance without digitally competent library staff and services, and that libraries must act together with faculty and students to create and sustain the necessary competencies. Within a year of my arrival, the DLF had articulated its aim for digital libraries to “provide the resources, including the specialized staff, to select, structure, offer intellectual access to, interpret, distribute, preserve the integrity of, and ensure the persistence over time of collections of digital works so that they are readily and economically available for use by a defined community or set of communities.” The DLF had also defined a detailed program agenda designed to integrate digital materials into the fabric of academic life, stimulate the development of core digital library infrastructure, and develop the organizational support for effectively managing digital libraries.[1]

While the outlines of these original aspirations have proved remarkably durable, much has also changed in the intervening 20 years. Digital skills in libraries, as well as among faculty and students in all disciplines, have measurably grown. In addition, the core infrastructure has also developed substantially, with universities and libraries now dependent on a host of new businesses providing digital tools and information services. With this growth and development, the priorities for digital libraries and digitally inflected research and education have correspondingly shifted. Among other issues, which I outline below, attention is needed now among libraries, not only to the urgency of preserving digital information, which Carol Mandel articulates so well elsewhere in this issue, but also to the shared financing and maintenance of the infrastructure and to extending its reach to a much broader segment of the citizenry.

The Scholarly Communications program was new to Mellon when you were hired. What were some of the major challenges you saw when you started to shape the program, and how did you address them? How has the program evolved over the years, and have there been surprises?

Before it hired me, the Mellon Foundation had a long and steady interest in the processes of scholarly communications, which depend on the vitality of research libraries and scholarly publishers and their roles in preserving, distributing, and providing access to the scholarly record. After the Foundation was established in 1969, its first awards included a grant to support the role of libraries in scholarship. The Associated Colleges of the Midwest received funds to collaborate with the Newberry Library and establish a seminar in the humanities. In 1976, at the height of the energy crisis, the Foundation initiated a series of grants to establish the Research Libraries Group, which helped foster cost savings, mainly in the cataloging operations of the largest of the nation’s academic libraries. Also, in 1976, it entered the field of library preservation, with an award to the New York Public Library. And between 1972 and 1982, the Foundation made 84 grants to university presses, helping them weather the financial crises of the period.

By the early 1990s, the Mellon Foundation had sharpened its interest in scholarly communications, focusing on the market for scholarly monographs. It issued a detailed empirical study showing how the increasing costs of serials reduced the ability of libraries to purchase monographs.[2] Based on these findings, the Foundation launched a series of studies investigating the financial health of independent research libraries,[3] followed by a funding initiative to shore up their endowments. It also began to explore the application of digital technologies to the scholarly communications process, “from the electronic publication of works of scholarship, to ways of organizing and cataloging materials, to the provision of electronic access to the source materials for doing scholarship.”[4] These explorations resulted, in part, in the creation of JSTOR and Project Muse, and in the support of art imaging projects that eventually led to the formation of Artstor in the early 2000s. The complexity of issues that these studies and initiatives revealed convinced the Foundation to establish a standing program dedicated to scholarly communications. The Foundation hired me to direct this program.

Over the last 20 years of Scholarly Communications grantmaking, the Foundation invested nearly $750 million in almost 1,800 grants. Understanding the trajectories, nuance, import, and effects of this investment would require a very full and detailed analysis, which I cannot undertake here. Instead, I offer a rough overview of the challenges that the program faced and tried to address by positing three general arcs of grantmaking.

First, recognizing the astounding success of JSTOR across fields in the humanities, the program began systematically to explore how digital technologies could be even more useful in specific fields. It made a significant investment in the field of art history with the formation of Artstor as a repository and point of access to digitized images. At the same time, the Scholarly Communications program identified leading scholars (mainly in the United States, Canada, and Europe, including the United Kingdom) who would undertake the explorations in other fields. Over time, the fields in which the program supported vigorous explorations of the uses of digital technology included, in addition to art history: musicology, archaeology, American history, literary studies, Afro-American studies, classics, medieval studies, early modern studies, and philosophy.

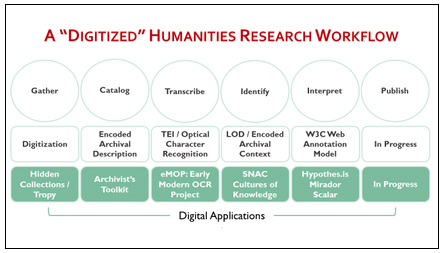

It was surprising at the time how these probes and experiments provoked such intense and robust interest from the scholarly community. In retrospect, this grantmaking activity helped support a broader interest in what became known as the “digital humanities.”[5] From these various projects, needs clearly emerged for a variety of digital tools, standards, and services for scholars to use to advance their research and teaching. These needs gave rise to a second arc of grantmaking focused specifically on these tools, standards, and services. The list is long and varied, but over time they have taken shape as a coherent infrastructure that supports the key tasks in the workflow of a humanities researcher. The following diagram offers a general schematic of the functional elements in such a workflow, whereby a scholar gathers relevant sources, organizes and catalogs them, transcribes and possibly translates them, identifies key elements within the sources,

and then annotates and interprets them. The second line in the diagram suggests how this workflow is being translated into the digital environment through the application of digital processes and standards. The third line identifies a set of tools developed with Foundation funding, and with which these process and standards can now be implemented into operational digital workflows. As indicated, the publishing component is still under development as part of the Scholarly Communications program’s digital publishing initiative, launched in 2014. Perhaps this schematic suggests more optimistically than is appropriate how fully the digital infrastructure has matured, and it certainly has not progressed solely with Mellon Foundation support, but it does indicate how far digitally enabled scholarship in the humanities has come since the pioneering days in the early 1990s when the University of Virginia established the Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities.

A third arc of grantmaking over this 20-year period has focused on digital preservation. Early on, the Scholarly Communications program provided support to establish Portico and LOCKSS (“Lots of Copies Keeps Stuff Safe”) to preserve digitally published journals. Subsequent funding has supported the preservation of audiovisual materials, social media, born-digital materials, digitally published books, and software.

As you depart the Foundation, what are the “grand challenges” you see in scholarly communication? What needs to be done to address them? What are the key aspects of higher education that could facilitate this vision, and what might impede it?

It is a mark of great accomplishment for the academic community, including its libraries and publishers, to now have in place the key infrastructural elements of a digitally reengineered humanities research workflow. The accomplishment is especially notable at a time when the growing press of digital media and the threat of disinformation requires a citizenry fluent in the critical use of digital tools and content. The academic community will have to determine the extent to which this accomplishment marks a point of conclusion in the evolution of scholarly communications in the digital world and the extent to which it provides the ground on which to build further. Here I summarize several ideas that might factor into this determination.

First, perhaps the biggest challenge facing the academic community is the need to strengthen this new digitally enabled scholarly communications system by ensuring that it meets the needs of a more diverse range of publishers, libraries, and archives; this range includes public libraries and small community-based archives as well as independent scholars and adjunct faculty, not only in the global north but also in the global south. An important part of the strategy in meeting this critical challenge would be to encourage the development of systems for memory institutions that make use of standard web technologies, such as linked data, rather than rely on proprietary systems that isolate them from the wider world of online information.

Second, while new development of the infrastructure may not hold the priority that it once did, there are gaps that may call for prudent investment in the development of certain new components. As mentioned in the previous point, greater investment in ways to exploit the benefits of linked data would address one of these critical gaps. As another example, computer engineers have posited that the development of new apparatus to connect applications at each point in the workflow—for example, from “gather” to “catalog”—could greatly improve the user experience. The infrastructure also needs more vigorous testing and development with varied genres of content, such as poetry, and methodological approaches associated with these genres.

Third, given a basic, working infrastructure, the academic community must raise the visibility and profile of efforts to maintain the tools and services, and of the maintainers needed to keep the components in good working order. Financial sustainability is a critical element of maintenance and the academic community desperately needs a more diverse and robust set of concepts and mechanisms in its financial quiver to pay for the capital and operating costs of the digital tools and services in the new order of scholarly communications.

Fourth, related to the maintenance of new tools and services is the ongoing problem of the preservation of content. There is a looming “memory hole” in the cultural record as published works are increasingly distributed not in copies that could be independently preserved, but in highly centralized databases owned by commercial companies. The preservation of books, journals, newspapers, film, and other media are all threatened by this concentration of cultural wealth in fewer and fewer hands that care about preservation only if there is continued commercial profit.

Fifth, as the academic community incorporates and maintains new media and technologies in humanities scholarship, it must find ways systematically to interrogate them. What would a humanities curriculum be for machine learning? How could algorithm-based services become more transparent? What are ethical uses of social media? How should researchers in the humanities treat personally identifiable information, medical records, and other private materials? What about culturally sensitive information? What is the right balance to strike between digitally preserving the cultural record and appropriating intellectual and cultural property from its rightful owners?

Following on the previous point, I close this reflection with a brief comment on the challenges of intellectual property. In many ways, intellectual property is at the heart of scholarly communications. It is the “stuff” that is accessed, published, and preserved. Over the last two decades, there has been a vigorous and increasingly polarized debate in the academic community about making scholarly works available on an open access basis. Proponents of open access often invoke a justice argument, suggesting that open access is warranted because it favors audiences who have paid for research results with their tax dollars and should not have to pay again. However, an alternative argument is that open access is unjust because it exacerbates, rather than diminishes, inequality in scholarly communications. That is, it allows Google and already wealthy publishers, like Elsevier, to further enrich themselves with free content on which they build search and lucrative, fee-for-service analytical services. Further, and this argument is of particular concern to scholars in the humanities, by making works of authorship free to read but costly to publish, open access favors wealthy, grant-rich disciplines, and unjustly consigns poorer scholars and underserved people to a class of knowledge producers increasingly unable to express their abilities and disseminate their contributions. There will surely be an important and ongoing place for open access in the wide world of scholarly communications, but the unanticipated and worrisome consequences of its application mean that there will also be a continuing need for much caution in responding to passionate calls for a “default to open.”[6]

[1] Donald J. Waters, The Digital Library Federation: Program Agenda, July 1, 1998. Washington, DC: Digital Libraries, A Program of the Council on Library and Information Resources.

[2] Anthony M. Cummings, Marcia L. Witte, William G. Bowen, Laura O. Lazarus, and Richard H. Ekman, University Libraries and Scholarly Communications (Washington, D.C.: Association of Research Libraries for The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, 1992).

[3] William G. Bowen, Thomas I. Nygren, Sarah E. Turner, and Elizabeth A. Duffy, The Charitable Non-Profits: An Analysis of Institutional Dynamics and Characteristics (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1994); Jed I. Bergman, Managing Change in the Nonprofit Sector: Lessons from the Evolution of Five Independent Research Libraries (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1996); Kevin M. Guthrie, The New-York Historical Society: Lessons from One Nonprofit’s Long Struggle for Survival (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1996).

[4] William G. Bowen, “Preface.” In Technology and Scholarly Communication, Richard Ekman and Richard E. Quandt, eds. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), p. ix.

[5] Donald J. Waters, “An Overview of the Digital Humanities.” In Research Libraries Issues 284, pp. 3-11. Available at https://publications.arl.org/rli284/3. Donald J. Waters, “Digital Humanities and the Changing Ecology of Scholarly Communications.” International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing 7 (March): 13-28.

[6] Donald J. Waters, “Restrictions in the Age of Open.” Shared Experiences Blog, December 9, 2015. New York: The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Available at https://mellon.org/resources/shared-experiences-blog/restrictions-age-open/.

Are We Doing Enough to Manage and Preserve Born-Digital Content?

The many challenges of managing and preserving digital content are well-known to cultural memory institutions. Institutions have become adept at digitizing and reformatting important content and ensuring its long term access. At the same time, the nature, scale and policy complexities of content that is born digital are presenting an even more radical shift in demands and expectations. An overwhelming amount of the knowledge, documentary evidence, and creative expression produced today originates in digital formats—from news reports to media to personal papers. While important initiatives have emerged to keep selected born-digital content accessible, in comparison to collecting policies of the analog age, we are preserving only a small portion of what exists. Is it enough?

CLIR Presidential Fellow Carol Mandel is investigating this question in a study of the societal and institutional frameworks that collect and preserve born-digital documentary evidence. She finds that while we continue to make impressive progress in addressing the daunting technical demands of preserving digital materials, our ability—and impetus—to collect born-digital content lags far behind likely future needs for the documentation of today’s world. The decision to collect is an essential pre-requisite to preservation and enduring access.

Mandel has completed an initial framing chapter of her research, outlining the significant disparities between the traditional roles and expectations of memory institutions and the disruption presented by new forms of born-digital content. “Society largely takes for granted that its heritage is being preserved by this reliable network of institutions,” she writes, but they now face formidable obstacles. “The challenge of preserving digital-only content needs, somehow, to be met within a feasible economic and institutional context.” As Mandel illustrates, that context does not now exist, and we are facing a complex societal problem.

Subsequent work to be released over the coming months will expand the framing work to consider legal, policy and priority issues, and then delve more deeply into approaches for collecting selected areas, such as news, social media, web content, publishing output, and personal and community archives.

CLIR hopes that Mandel’s work will spark discussions that, at a minimum, lead to shared understandings of priorities and expectations about what can and should be captured and preserved. Ideally, we hope it will stimulate ongoing community engagement and creative problem solving. Collecting and preserving born-digital content requires new strategies, partnerships, and initiatives that only broad and diverse community perspectives can address.

CLIR is soliciting comments on chapter one at comments@clir.org. A series of questions is included at the end of the chapter to frame discussion. Mandel will also lead a panel at the DLF Fall Forum, “The Story Disrupted: Memory Institutions and Born Digital Collecting.” She and Clifford Lynch will also do a breakout session on this work at the December CNI Member Meeting.

New Releases

The Foundations of Discovery: A Report on the Assessment of the Impacts of the Cataloging Hidden Collections Program, 2008–2019, by Joy M. Banks. This report presents the results of a comprehensive analysis of final reports from all 128 projects funded through the Cataloging Hidden Collections program. Running from 2008–2014 with funding from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the program granted more than $27.4 million to academic, cultural heritage, and other collecting institutions to catalog “hidden” collections of high scholarly value. The program brought more than 4,000 collections to light in more than 160 institutions in the United States and Canada.

The report describes the methods and findings of the analysis, including cataloging outputs, as well as the impact on hiring, policies and procedures, communication tools, and research and outreach. According to the study, nearly 98% of respondents reported an increase in the use of materials cataloged or processed as part of a Hidden Collections project. Nearly 65% reported an increase in users or visitors to the collections, and 92% reported an increase in reference queries. Some 44% reported that, because of these grants, cataloged materials were used in publications and other projects.

The report draws four main conclusions about the program:

- The investment made in cataloging materials across the United States and Canada made a significant impact on the culture of collecting institutions and the attitudes held about the importance of historic collections and the people that work with them.

- Recipient institutions represented a diversity of types and sizes of gallery, library, archives and museum (GLAM) organizations, which allowed for an impressive breadth and depth of item types made accessible through the program.

- Long-term sustainability of online catalogs is challenging for many of these institutions. Library support organizations like CLIR must determine what, if any, resources or advice they can offer to constituents facing difficult financial decisions affecting the availability of collection descriptions over time.

- In an increasingly digital research environment, there is a pressing need for search and discovery systems that bring together descriptions of both physical and digital artifacts so that researchers can learn about them alongside one another.

And two new resources from DLF Working Groups:

Technologies of Surveillance Group Advocacy Action Plan, by Eliza Bettinger, Mahrya Burnett, Michelle Gibeault, Yasmeen Shorish, and Paige Walker. This document will assist librarians who want to communicate about the sensitivities of library patron data with those serving in decision-making roles. As librarians discuss how patron data is used and shared in wider institutional and societal contexts, it is essential to understand why librarians choose to share and analyze some patron data, while at other times choose to protect, limit the collection of, and purge that data. In many cases, libraries may be mandated by their governing bodies (e.g., university administrators, city councils, boards) to provide data related to the use of the library and its systems and content. Librarians may struggle to balance the potential usefulness of patron data as it relates to student success, library funding, advocacy, and assessment with concerns over patron privacy.

#DLFteach Toolkit 1.0: Lesson Plans for Digital Library Instruction. This openly available, peer-reviewed collection of lesson plans and instructional strategies is the result of a project led by the professional development and resource sharing subgroup. The publication emerged from #DLFteach workshops, office hours, Twitter chats, and open meetings, where community members and digital pedagogy practitioners expressed interest in having lesson plans and session outlines that they could use as a jumping-off point for their own instruction and adapt for local contexts.

The toolkit includes 21 open, peer-reviewed lesson plans in the areas of:

- Critical information literacy and digital publishing

- Data and maps

- Project development and management

- Text analysis and (en)coding

- Digital exhibits and archives

All lessons include learning goals, preparation, and a session outline. Additional materials—including slides, handouts, assessments, and datasets—are hosted in the DLF OSF repository as well as being linked to from each lesson.

Follow the DLF Forum and Affiliated Events

If you can’t attend the 2019 DLF Forum or affiliated events in Tampa this month, you can still follow the action through selected livestreamed sessions, Twitter, and community notes.

Marisa Duarte’s opening keynote will be livestreamed October 14, from 9:00–10:30 am ET. Duarte, assistant professor at the School of Social Transformation at Arizona State University, will speak on “Beautiful Data: Justice, Code, and Architectures of the Sublime.” The Forum’s closing plenary, “A Call to Action,” will also be livestreamed October 16, from 11:45–12:30 pm ET.

The opening plenary and keynote for Digital Preservation 2019, featuring Alison Langmead, will be livestreamed October 16, from 2:00–4:00 pm ET. Langmead, who holds a joint faculty appointment at the University of Pittsburgh between the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences and the School of Computing and Information, will present “Sustainability is Not Preservation.”

Livestream links will be available at https://forum2019.diglib.org/livestream-recordings/.

Preceding the Forum on October 13 will be a Learn@DLF workshop day. A schedule for the Forum and affiliated events is available at https://forum2019.diglib.org/schedule/.

We invite you to also follow along on Twitter (#DLFforum, #LearnatDLF, and #DigiPres19) and to view community notes at http://bit.ly/2019DLF. The title of each document corresponds to the session code on the schedule.

CLIR is also seeking feedback from community members about DLF’s future direction. If you cannot attend the Forum but would like to speak with Joanne Kossuth, who is leading the review of DLF, please contact her at joanne.kossuth@gmail.com to arrange a time to talk after the Forum.

Call for Host Institutions: Postdoctoral Fellowship Program

CLIR is currently soliciting host institutions for 2020-2022 Postdoctoral Fellowships.

October 21 is the deadline to apply as a host for Postdoctoral Fellowships in Data Curation for African American and African Studies. These fellowships, which are supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, are for recent Ph.D.s with expertise in any aspect of African American and African Studies; salaries, a portion of fringe benefits, and educational benefits are fully funded through CLIR for selected hosts. Host institutions may include any academic, independent, public, or government library, archive, or museum, or any partnership or consortium made up of the same, provided it has demonstrable need of the fellow’s subject expertise to pursue a project or initiative commensurate with its mission.

Applications are accepted on a rolling basis for Postdoctoral Fellowships in Academic Libraries, though are encouraged well before the fellowship candidate deadline of January 10, 2020. These fellowships are open to any discipline and are flexible within the program’s overall goals and guidelines. They are designed and funded by hosts, who also pay fees to CLIR to help cover the costs of the fellows’ participation in program activities. Host institutions may include any academic, independent, public, or government library, archive, or museum, or any partnership or consortium made up of the same, provided the organization has a demonstrable need of the fellow’s subject expertise to pursue a project or initiative commensurate with its mission and in alignment with this program’s goals.

More information on host opportunities is available at https://www.clir.org/fellowships/postdoc/hosts/.