Number 124 July/August 2018

ISSN 1944-7639 (online version)

Contents

The Black Bibliography Project

Email Archiving Comes of Age

CLIR Names Curatorial Advisors to Digital Library of the Middle East

Learning from Hidden Collections

Follow the DLF Forum and Affiliated Events

Staff Updates

CLIR Issues is produced in electronic format only. To receive the newsletter, please sign up at https://www.clir.org/pubs/issues/signup. Content is not copyrighted and can be freely distributed.

Follow us on Twitter @CLIRNews, @CLIRHC, @CLIRRaR @CLIRDLF

Like us on Facebook @CLIRNews

The Black Bibliography Project

—by Jacqueline Goldsby and Meredith McGill

Jacqueline Goldsby is CLIR Presidential Fellow and Professor of English & African American Studies at Yale University. Meredith L. McGill is Associate Professor of English and Director of the Graduate Program at Rutgers University.

Plus ça Change…

Over the last 30 years, the study of African American literature has grown rapidly in size and importance. It is now a vital field of specialization in any English department of merit. And yet scholars of African American literature still lack thorough bibliographical knowledge of many of the texts at the heart of the field. Why has this development occurred, and what has been the intellectual impact?

The opening of the literary canon to writers of color coincided with the decline in the practice of scholarly bibliography—the systematic study of books as physical objects. This divided path has produced significant unevenness in the resources available to scholars of African American (and, consequently, American) literature. Indeed, the near-disappearance of bibliographic studies from U.S. literary criticism arguably reinstitutes a color line that needlessly hampers the growth of African American literary and book history studies.[1]

For instance, criticism of canonical white U.S. writers continues to be buttressed by authoritative accounts of the production and transmission of Anglo-American and Western European texts. Two examples come quickly to mind: the groundbreaking Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson electronic archives rest on decades of meticulous, old-fashioned bibliographic scholarship. By contrast, scholars studying African American and Black Diaspora literatures are often forced to sort out complex and confusing publication histories on their own, because standard bibliographic sources often don’t include Black writers in their canonical range. To cite one key example: the nine-volume Bibliography of American Literature (BAL)—the gold standard reference tool in the field—provides comprehensive bibliographic information for American authors of belles-lettristic works who died before 1930. Due to a narrow definition of literariness, an emphasis on elite print sources, as well as ignorance of a wide range of African American writing, only a single African American author—Paul Laurence Dunbar—earned entry into its ranks. This oversight sharply limits the utility of this important reference tool for African Americanist students and scholars.

The recent boom in Book History and in the digital remediation of African American writing has, thankfully, begun to correct such imbalances. Maryemma Graham’s Project on the History of Black Writing collects publication information on over 1,000 novels written by African Americans between 1853 and 1990. Elizabeth Maddock Dillon’s and Nicole Aljoe’s Early Caribbean Digital Archive collects digital versions of rare and scattered texts from across the Caribbean, with a focus on the recovery of black voices embedded in colonial writing. The Black Press Research Collective serves as a hub for information and scholarship on the role of newspapers in the black diaspora.

As the recovery and digitization of black print proceeds, however, the lack of a centralized repository of reliable information about the printed objects at the heart of these projects becomes more acute. On the one hand, the proliferation of digital surrogates threatens to outpace the training of scholars of African American literature in basic book historical and bibliographic techniques. On the other hand, a long, distinguished history of bibliophilia and bibliography among scholars, librarians, and private collectors who specialize in African American print culture precedes digitization’s interventions.[2] How, then, might the traditions of descriptive bibliography be revived, and how might they transform present-day African American literary and book history studies?

Indices of Change

The two of us joined forces to launch the Black Bibliography Project (BBP) to take up this task, with two main goals guiding our work.

First, we aim to create authoritative web-based bibliographies of major African American authors, periodicals, and publishers. We plan to collect, standardize, and make electronically available reliable bibliographic information on the works of canonical African American authors. Working in partnership with a national network of libraries and archival repositories that specialize in African American print culture and its histories, we want to build a digital foundation for bibliographic inquiry and literary scholarship, producing (1) a web-based tool to assist scholars in collecting physical descriptions of books and cheap print formats (such as pamphlets and periodicals) scattered across numerous rare book collections; and (2) a prototype for web-based presentation of bibliographic information that accommodates both traditional bibliographic description as well as visual evidence of formats, illustrations, binding styles, printers’ locations, and networks of reception.

Second, we aim to train the next generation of scholars of African American literature in book history and principles of bibliographic description. We hope to convene scholars, curators, catalogers, and librarians and teach them the material aspects of African American literary publishing. We would also use these workshops to develop protocols for the bibliographic description of African American print materials. We will ultimately organize the colleagues we teach into research clusters that will collaborate with us to compile the bibliographic data needed to develop a digital, open access bibliography of African American literary works.

Gauging the Task

To begin our work, we partnered with Yale’s Beinecke Library and Rutgers’ School of Arts and Sciences to convene three intensive summit conferences; each helped us gauge more precisely how to begin addressing the “bibliographic situation” in African American literary studies and book history.[3]

We began with two gatherings. In March 2017, we met with librarians, curators, and digital humanists who have been thinking about the problem of corporate digital resources and about gaining access to metadata about books currently locked up in multiple proprietary library cataloging systems. In October 2017, we invited librarians, curators, and catalogers who specialize in the collection, classification, and preservation of black-authored texts, along with scholar-experts in African American literature and book history, to examine prior models and practices of bibliographic description in African American literary studies.

These initial summit conferences taught us three invaluable lessons. First, the challenge of black bibliography can’t simply be addressed technologically by the digital remediation of print resources. As one participant, Tim Thompson, Rare Book Cataloger at Yale’s Beinecke Library, reminded us, our cataloging practices are not simply racist, they are white supremacist. One can’t search library catalogs for “whites as authors;” white writers remain the invisible default category against which others are defined, classified, and sorted. If the norms of Black authorship and print culture were to define cataloging’s data fields, what might those categories be?

Second, Kathleen Bethel, African American Studies librarian at Northwestern University, asked whether it would be possible to design a born-digital bibliography that would operate in an “Afrocentric” way—guided by the principles and practices of black writers, publishers, librarians, and collectors, rather than shoehorning African Americans’ complex relations to print into norms of white bibliographic practice (e.g., emphasizing elite print, major publishing houses, and first editions). Indeed, how might focusing on black-authored texts challenge the norms of bibliographic description as such?

Finally, how might a consortium approach to collecting information about black print—one that leveraged the collections and the cataloging strengths of multiple repositories—amplify our work and help to knit together librarians, curators, and scholars in a community of mutual interests?

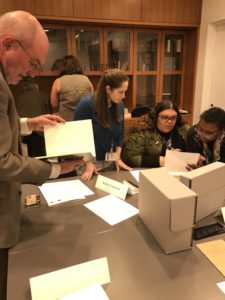

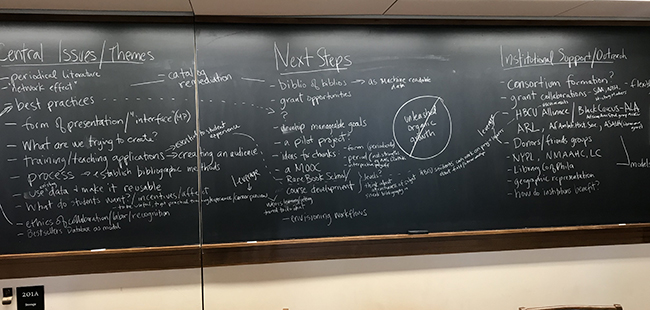

In May 2018, we gathered a smaller group of graduate students from Rutgers and Yale, staff catalogers from the Yale and Beinecke Libraries, along with key scholar-partners, to take up Tim Thompson’s and Kathleen Bethel’s charge. Bibliographic expert and editor and compiler of the final three volumes of the BAL Michael Winship led the group through an immersion demonstration of descriptive bibliography, to ensure we were all on the same page (so to speak) with the discipline’s fundamentals. We then staged a hands-on, crowd-sourcing exercise, in which participants examined a range of Black print materials from the Beinecke’s holdings to tease out preliminary “Afrocentric” categories we might use as metadata. We concluded with the Yale/Beinecke catalogers providing a first and important tutorial in metadata collection options. We aim to compare those results—the crowd-sourced categories with established metadata conventions—to produce a fresh descriptive scheme which we will test across a range of Black print materials. Our end goal: to take the BBP’s pedagogy to a nationwide scale.

Bringing Objects Closer Than They Appear

With African American literary studies’ continued growth and flourishing, scholars need consistent, reliable bibliographic descriptions of Black-authored print sources. While our summits have convinced us that a digital database can fill this gap, we’re deeply humbled by the scope of work that remains ahead. In order to reckon with Black print culture and its modes of production, dissemination, and use, bibliographic and cataloging practices will have to change. Our hope is that by collaborating with curators, librarians, and catalogers, we will generate new ways to describe Black print culture in all its richness and diversity, and that bibliographic studies will gain wider relevance to African American and U.S. literary studies broadly speaking.

[1] For a still trenchant assessment of the field, see Leon Jackson, “The Talking Book and the Talking Book Historian: African American Cultures of Print—The State of the Discipline,” Book History 13 (2010): 251-308.

[2] On the 19th and early 20th-century practitioners and protocols, see Elinor Des Verney Sinnette, W. Paul Coates, Thomas C. Battle, eds., Black Bibliophiles and Collectors: Preservers of Black History (Washington, DC: Howard UP, 1990).

[3] This phrase comes from scholars Marguerite Bicknell and Margaret McCulloch, who decried the lack of adequate bibliographic tools in the nascent field of African American studies to the chief curator of the Schomburg Collection at the New York Public Library’s 135th Street Branch. See Bicknell’s and McCulloch’s letter to Lawrence D. Reddick, Sept. 20, 1942, Schomburg Center Records, Box 1, Folder 1a.

Email Archiving Comes of Age

—by Christopher Prom and Kate Murray

Editor’s note: The authors co-chaired the Task Force on Technical Approaches for Email Archives, whose report CLIR published last week. Christopher Prom is assistant university archivist and Andrew S. G. Turyn Professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Kate Murray is digital projects coordinator at the Library of Congress.

For many of us, email comprises the journal of our personal and professional daily life. We use it to exchange quick notes and detailed information; we make plans for business meetings or casual lunches; we catch up with family, friends, and colleagues; we give opinions, make decisions, and discuss the news of the day. Even with the rise of other social media platforms and instant messaging applications, email remains in widespread use today with a solid future ahead. But perhaps more important for archives and libraries, email has a long history of adoption, and many collecting institutions receive material long after its creation date. Just like the bundles of letters in an attic, petabytes of email are cueing up in professional and personal accounts. But will they ever pass through the virtual doors of archives around the world?

As the Mellon Foundation and the Digital Preservation Coalition-sponsored Task Force on Technical Approaches for Email Archives discovered over the course of its work, email is fundamentally a different beast than traditional paper-based personal papers and letters. The problems of email archiving arise from how contents are organized, or disorganized, before they are captured by archivists. In a nutshell, the complexity of email archives and the scope of attachment formats—combined with the sheer scale and volume of email collections, and the paucity of robust tool sets—make email archiving a potentially daunting task.

By assessing current efforts to preserve email, articulating a conceptual and technical framework, and constructing a community agenda for future work, the task force members developed a tiered set of recommendations focused on two complementary areas: (1) community development and advocacy, and (2) tool support, testing, and development. In The Future of Email Archives, the task force lists suggested activities for each area. These include both low-barrier actions, which the community can start addressing immediately, and projects that require more planning and funding.

By assessing current efforts to preserve email, articulating a conceptual and technical framework, and constructing a community agenda for future work, the task force members developed a tiered set of recommendations focused on two complementary areas: (1) community development and advocacy, and (2) tool support, testing, and development. In The Future of Email Archives, the task force lists suggested activities for each area. These include both low-barrier actions, which the community can start addressing immediately, and projects that require more planning and funding.

One of the most challenging issues from an archival perspective stems from email’s ubiquity: because it is so integrated with our daily life, email collections are ripe with personal, sensitive, and private information. Archivists and curators need powerful and flexible open-source tools to automatically identify, remove, redact, and restrict personally identifiable information (PII) or otherwise sensitive information—a process commonly known as sensitivity review.

The onus on the email archiving community is to build trust for both the donor and researcher communities through strong policies and actions with respect to accessioning, appraisal, and preservation, supported by scalable and cost-effective technologies that enable sensitivity review, redaction, and access. While search and discover functions exist for structured classes of PII such as Social Security numbers and phone numbers, this functionality does not extend to less-structured information such as education or health records. Also absent is reliable search functionality for less defined “fuzzy” searches that don’t rely on specific terms. Without these capabilities, donors are reluctant to include email collections in potential acquisitions, and historians and other researchers struggle to interact with the data in a meaningful way, if they can even get access to the data.

Cost effectiveness is the key concept here. Email archiving functionality already exists but it’s most active in proprietary software tools typically used by the legal community for eDiscovery and declassification services. It is out of reach for many on the archiving side. The challenge is two-pronged: (1) improve the tools, and (2) make them widely available through open source development and sustained management efforts.

On the “improve the tools” side, natural language processing (NLP) applications and machine-learning software could be enhanced to improve the ability of collections managers to identify and extract more nuanced entities from the archive. Current NLP workflows rely on named entity recognition to identify just certain data types, such as persons, corporations, and places, even offering some comparisons against specific categories in Wikipedia.

On the “more widely available” side, the goal is to open both the software code and access to the improved toolsets outside of closed or proprietary systems. Focusing on open source development would allow a transparent and adaptable development framework. But open source does not mean unstructured and unsupported.

All is not doom and gloom. The report demonstrates that all archives—from the smallest-staffed unit allied with a local history society to the largest academic or government archives—can take steps to preserve email. The key lies in defining a target storage format, then leveraging current tools and services to move email from its current storage locations into a repository infrastructure. Since mail transport and exchange operate via a standardized, well-known set of protocols, archivists can chain together tools to capture and process collections.

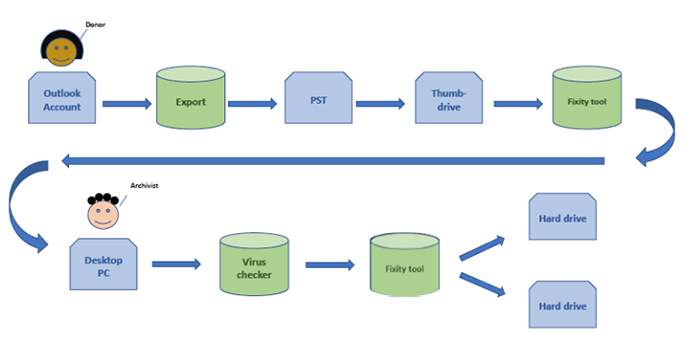

One of the most valuable sections of the report is the description of tools and workflows. These build on each other from simple to complex. Preserving the bit stream of messages in a format like PST—the proprietary but open format that Outlook uses to export messages—is a good first step. The following figure illustrates this process at work.

Processing email using this or a similar method (perhaps converting to a format like MBOX and saving attachments in their original binary formats) leaves open the possibility of applying more complex approaches later. The report provides many ideas and workflows to do just that, whether the repository’s goal is migration, emulation, or a combination of both.

Today, email is present in many of the most prominent news stories and is frequently cited in the latest exposés. But the first draft of history does not need to be the last word. And this brings us to perhaps the core takeaway from the task force’s work: archives and libraries are now primed for success in preserving email archives. Tools are maturing, but they just need a little boost. With some additional support, work, and community building, we can and will move toward greater interoperability and ease of use for all.

CLIR Names Curatorial Advisors to Digital Library of the Middle East

CLIR has named five curatorial advisors to the Digital Library of the Middle East (DLME):

- Saif Abdullah Al-Jabri, director, Information Center, Sultan Qaboos University Library, Oman

- Najwa Adra, anthropologist, Yemeni Intangible Cultural Heritage

- Mariette Atallah, head of Collection Development Department, Jafet Library, American University in Beirut

- Ryder Kouba, digital collections archivist, American University in Cairo

- Mariam Zaki, information specialist/librarian and PILOT coordinator, Cairo Urban Resource Library (CURL) at Cairo Lab for Urban Studies, Training & Environmental Research (CLUSTER)

The curatorial advisors will help identify and prioritize records for federation during the continuing design phase of the DLME platform. This expansion is expected to launch in 2020. The curatorial advisors will help ensure that the DLME includes representative records from all phases of the region’s history and all major languages, and that images are available in as many multimedia formats as possible. CLIR Distinguished Presidential Fellow Elizabeth Waraksa is coordinating the group’s work.

The DLME is envisioned as a non-proprietary, multilingual library of digital objects providing greater security for, preservation of, and access to digital surrogates of cultural heritage materials.

“The appointment of curatorial advisors marks a critically important phase of the DLME, a project conceived as a dynamic digital environment in service to the sustainability of and access to the cultural heritage of the Middle East,” said CLIR President Charles Henry. “These distinguished advisors will assure that DLME content, tools, and applications align with and exemplify regional priorities and aspirations.”

CLIR and its Digital Library Federation (DLF) program are working with technical partners at Stanford University to develop the DLME platform, with grant support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The project builds on experience gained in developing the DLME prototype, announced in January, which was supported with funding from the Whiting Foundation, and on regional partnership building and exploration of governance models in an earlier planning phase supported by Mellon. Among CLIR’s key collaborators are the Qatar National Library and the Antiquities Coalition.

An Arabic version of the announcement is available at http://bit.ly/2nUXEF2.

Learning from Hidden Collections

—by Joy Banks and Christa Williford

As the remaining Cataloging Hidden Special Collections and Archives projects draw to a close, CLIR is preparing an in-depth report on the outcomes of this program. From 2008 to 2014 with the generous support of The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, CLIR awarded nearly $27.5 million through this regranting program to a wide variety of GLAM institutions in the United States and Canada to catalog collections of rare and unique materials. A retrospective assessment of all 128 projects began in early 2018. The assessment will comprise an analysis of recipient reports, the calculation of total quantities of materials processed and cataloged, and the findings of an online survey about the longer-term impacts of funded projects on participating organizations.

To date, the 170 unique institutions involved in the program have revealed more than 6 million items through the creation of more than 30,000 finding aids, 44,000 authority records, 304,000 MARC records, and 358,000 item-level metadata records. Recipients also reported outcomes other than cataloging—such as presentations, publications, and curriculum development—as well as common challenges such as finding and maintaining qualified staff, encountering unexpected technical difficulties when implementing new tools and systems, and adjusting project plans in order to deal with larger-than-expected quantities of material. Looking forward, CLIR hopes to apply lessons learned from this program to existing and future regranting initiatives, especially lessons about how description can be integrated with digitization, how to build and encourage sustainable access to materials, and how ethical staffing practices can be better supported through grant requirements. The remaining open projects will close in early 2019, and CLIR has plans to publish a public report in early 2020 that will include key findings and outcomes from the entire program. For the most current details on the assessment, visit CLIR’s website.

Follow the DLF Forum and Affiliated Events

If you can’t attend the 2018 DLF Forum or affiliated events in Las Vegas this October, you can still follow the action through selected livestreamed sessions, Twitter, and community notes.

Anasuya Sengupta’s opening Forum keynote will be livestreamed October 15, from 9:00 – 10:30 PDT. Sengupta, co-director and co-founder of Whose Knowledge? will speak on “Decolonizing Knowledge, Decolonizing the Internet: An Agenda for Collective Action.” The Forum closing plenary (on “Enacting the Mission” of the DLF) will also be livestreamed October 17, from 11:30–12:30 pm PDT.

The opening plenary and keynote for Digital Preservation 2018, featuring Snowden Becker, will be livestreamed October 17, from 3:15–5:00 pm PDT. Becker, program manager for Moving Image Archive Studies at UCLA, will present “To See Ourselves as Others See Us: On Archives, Visibility, and Value.” The Digital Preservation 2018 closing plenary will also be livestreamed October 18, from 4:20–5:00 pm PDT.

The opening plenary and keynote for Digital Preservation 2018, featuring Snowden Becker, will be livestreamed October 17, from 3:15–5:00 pm PDT. Becker, program manager for Moving Image Archive Studies at UCLA, will present “To See Ourselves as Others See Us: On Archives, Visibility, and Value.” The Digital Preservation 2018 closing plenary will also be livestreamed October 18, from 4:20–5:00 pm PDT.

Livestream links will be available at https://forum2018.diglib.org/livestream-recordings/

Preceding the Forum on October 14 will be the first Learn@DLF workshop day, as well as Civic Switchboard and Library Publishing Curriculum workshops. A schedule for the Forum and affiliated events is available at https://forum2018.diglib.org/schedule/. We invite you to also follow along on Twitter (#DLFforum, #LearnatDLF, and #digipres18) and to view community notes at http://bit.ly/DLFforum2018 (Forum) and http://bit.ly/digipres18 (Digital Preservation 2018). The title of each document corresponds to the session code on the schedule.

Staff Updates

Wayne Graham has been promoted to Chief Technology Officer, a position that increases his scope and reach within CLIR, enabling him to develop both short and longer-term enhancements to our digital infrastructure and work environment.

Development and Outreach Associate Lizzi Albert will soon become CLIR’s most far-flung employee, as she moves to England in September to start a two-year MFA in Acting program at the University of Essex. Although her CLIR responsibilities will be reduced, she will continue helping with the president’s scheduling and other administrative needs, coordinating CLIR’s semiannual Board meetings, and contributing to development and outreach research. We wish Lizzi all the best in her next chapter!