An Interview with Carol Smith at Christ Church Preservation Trust

In this post, CLIR Director of Global Strategic Initiatives Nicole Kang Ferraiolo interviews Carol Smith, of Christ Church Preservation Trust.

Where do you work and what do you do?

I’m the Archivist at Christ Church Preservation Trust, a non-profit organization to ensure the preservation, restoration, and maintenance of historic Christ Church, Neighborhood House, and the Christ Church Burial Ground in Philadelphia, PA.

Christ Church Preservation Trust and its partner institutions received a grant from CLIR’s Digitizing Hidden Collections program in 2017, which is currently underway. What is the focus of this collaborative project?

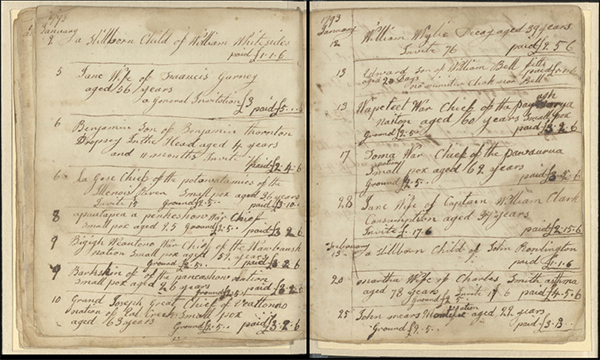

Eleven of the oldest congregations in the Philadelphia area have come together to digitize our 18th and 19th century records and create a digital database where they can be shared. These records provide a unique window into the political, social, and cultural developments in Philadelphia.

How did COVID-19 affect your project work?

We were beginning our third year of our CLIR Digitizing Hidden Collections grant project when Philadelphia and Pennsylvania announced large-scale closures of businesses and institutions due to COVID-19. Our records were a little more than 2/3 scanned and some of our manuscripts—Bishop White’s sermons—were still at the Athenaeum of Philadelphia’s regional digital imaging center. Luckily, they are as safe there as they are in the Christ Church archives.

Even more fortuitously Walter Rice, our IT consultant on this project, designed our project so that all of our work could be accessed remotely. Digital scans that Mike Seneca did at the Athenaeum were loaded into the Philadelphia Geo History website where our Metadata Archivist, Carly Sewell, could review them, and update the workflow process in AirTable. These scans and the accompanying metadata were then viewable through one unified website: www.philadelphiacongregations.org. Ultimately the records would be viewable through the American Theological & Library Association’s digital library; their digital archivist could harvest the files directly from the Omeka site.

How has online transcription helped you connect with your user communities at this time?

We had begun focusing on the transcription piece of this project last fall, holding a training session for members of our various congregations and early volunteers. Allan Hasbrouck, our volunteer in charge of transcription, developed guidelines based on Library of Congress standards and Walter Rice added a transcription portal to the www.philadelphiacongregations.org website, expanding on one he had designed for Christ Church in the earlier pilot project. Guidelines are prominently featured on the home page, and volunteers are required to register. Administrative staff have daily access to a transcription dashboard letting us know who’s working on what documents.

Once it was clear that we would be working remotely for some time we began to reach out to genealogists, members of the various congregations, and others we thought might be interested in helping with this phase of the project. Some of our project partners, notably the Athenaeum and ATLA, spread the word through their newsletters. Fifteen volunteers of all ages and interests came forward and we began to create an online community for them to keep them engaged. We began a Facebook group and planned virtual transcription work parties.

We had initially planned to transcribe the various baptismal, marriage, and birth records for all the available congregations but quickly realized it was more important to let our volunteers seek out the records they wanted to transcribe. It’s hard enough to plow through some of these idiosyncratic 18th century spellings and handwriting styles not to be interested in your work.

We hope to share through our private Facebook group the fun stories our volunteers uncover as they work their way through the decades—from the accounts listed for the purchase of rum as they built the Christ Church steeple to the Gloria Dei vestry minutes recording embezzlement by one of their own.

How might the experience of living through the COVID-19 pandemic change the way readers respond to the digitized records?

Perhaps as our members make their way through these original manuscript records they’ll recognize the challenges faced by our predecessors from the Yellow Fever and smallpox epidemics of the 18th century to the hardships posed by war. Philadelphia was close to the epicenter of the Revolution and occupied by the British in the winter of 1778. Recognizing that these 18th century Philadelphians suffered through eight years of war and our 19th century predecessors lived through the horrors of a civil war for four years may make our quarantine a little more bearable.

Editor’s note: This is the fifth piece in COVID (Re)Collections, a series exploring responses to the COVID-19 pandemic by library, cultural heritage, and information professionals. Stories are proposed by the authors/contributors and reflect their personal experiences and perspectives at the time of submission. Learn more about the series and share your own story here.